With AiW Guest: Leonie B. Predić, including a conversation with Fanny’s D’Or.

“You were the key to the doors of space, now you are a scar, a phase”

In Chad, listed by Saifaddin Galal’s 2023 research as the least gender equal country in sub-Saharan Africa (Statista), a new generation of female poets fights, voice against blade. With special thanks to Fanny’s D’Or…

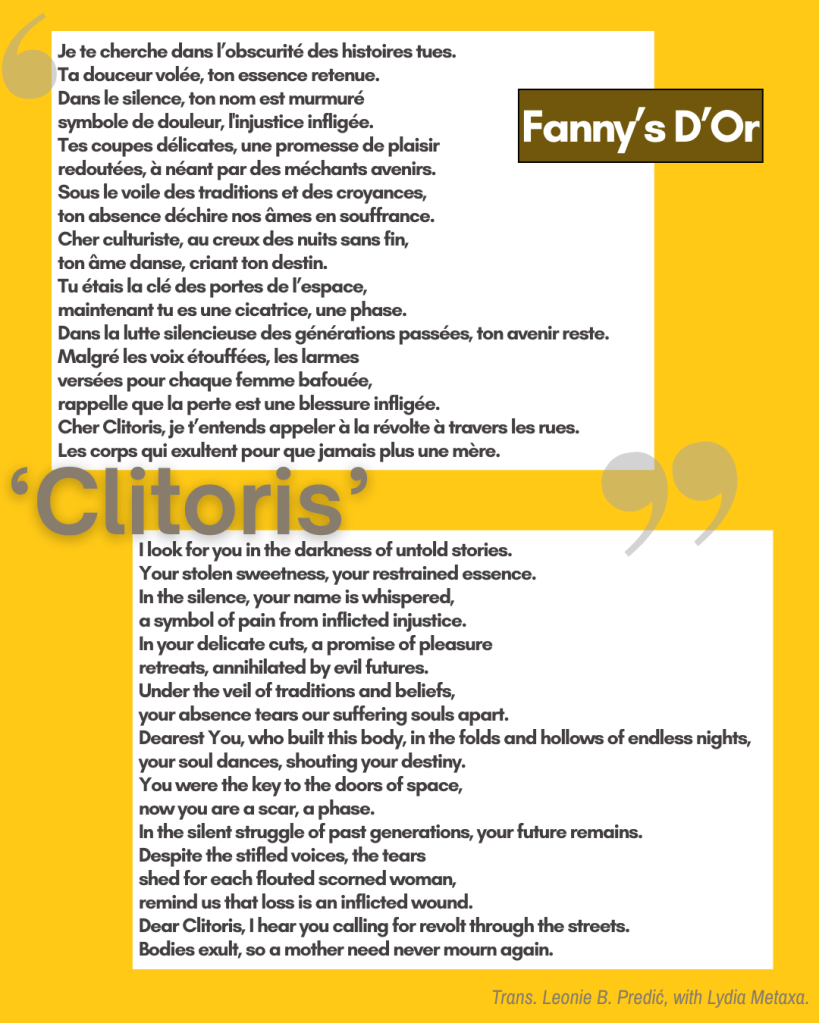

It’s dinner time, July 2024, and adverts are playing on a radio somewhere in the background while Chad’s official number one slameuse (woman slam artist) performs her cutting poem, ‘Clitoris’, to me. Bellies are full, dishes are piling up and will soon call for someone to scrub them clean; the radio station will take control again, and the programme will go back to normal, but not before Fanny’s D’Or has finished. I hear her voice, gentle, until it rises with strength and power– finally, she rips away the fig leaf over her muse, reveals it to us and calls to it directly:

“Dear clitoris, I hear you calling for revolt through the streets”.

In the capital of Chad, N’Djamena, slameuses like Fanny’s D’Or line up to take to the stage, clutching microphones and grabbing their crotches, reciting foul-mouthed poetry to crowds of young urbanites cheering them on while sipping on sodas and watching with wide eyes.

And as recent research in the field has recognised, Fanny’s, along with a growing number of others, invigorates a slam movement gaining force in francophone Africa, voicing a “body of popular knowledge that questions the status quo” (Mirjam de Bruijn and Loes Oudenhuijsen, ‘Female slam poets of francophone Africa: spirited words for social change’. Africa. 2021;91(5):742-767). In this movement, female francophone slam artists are on the rise, defying societal expectations in the unequal societies they speak out to, voicing their opinions and offering others the opportunity to do the same, as Fanny’s has said, “despite the darkness” (2017).

Slam artists often take on stage names or personas not dissimilar to pop icons. Here in Chad, they are equally often layered with a depth of meaning signalling their personal politics and values from the go. Fanny’s D’Or, a.k.a., Nodjikoua Dionrang Epiphanie, is no exception. Her chosen name brings self-empowerment in a country where nearly a quarter of girls under 15 are married off, forgotten or silenced: “Fanny is the diminutive of my first name and gold [(D’Or)] is a rare and valuable object that I love,” she reveals. In her piece ‘Clitoris’ (excerpted at the head of this article), Fanny’s reflects on her experiences with FGM, using slam as a medium of expression, therapy, and activism: “It is an oratorical art which is my enforcer and allows me to carry the voice of the voiceless.”

Redefining the political in the Chadian spoken word

Today, competitive French-speaking slam artists in Chad recite their poetry on the stages they make as they speak it out, in festivals, in bars, on the streets. Through often multi-faceted performances – that range from a cappella, to the inclusion of dance, some with evocative musical underscoring – they showcase their art and the timeliness of its messages. Central to this trajectory is the now annual slam festival held in the capital, N’Djam S’Enflamme en Slam (N’Djamena Burns With Slam), launched in 2013 by Chadian slam artist, Didier Lalaye.

Lalaye goes by the stage name of Croquemort – in translation, an undertaker, mortician, or pallbearer, but in common usage, usually pejorative with connotations of ‘killjoy’ or ‘wet blanket’. Plumbing the rich vein of metaphor, in an energy which captures the significance of ancestral presences, in performance, Croquemort sometimes wears a skull mask and a white scarf, traditional attire signifying Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead), rousing up the crowds that flock to his live acts. Likewise, more literally translated as “dead-biter” or “corpse-biter”, up until the last century in Belgium, the term referred to those gravediggers who, fearing burying a person alive, would bite a corpse’s little finger in order to wake up those who may simply have been sleeping.

In 2015, the satirical bite that inspires Croquemort’s voice and resonates in the festival blew up. He become an internationally recognised champion of slam in the Francophone world almost overnight with Cousin de l’UE (Cousin of the European Union), in which he bashes the double standards of European hypocrisy:

Ils ont Lepen et Sarkozy [/] Mais eux te parlent de Mugabé, [/] Ils ont les corses qui incendient [/] Et parlent de la Kabylie en fumée. [/] Ils ont les dissidents de l’IRA [/] Des attentats à Londres [/] Mais leurs télés filment la LRA [/] Et l’Ouganda qui s’effondre.

(Transcribed and translated by Voice4Thought)

They have Lepen and Sarkozy [/] But they only talk about Mugabe [/] They have Corsica which burns [/] but talk of Kabylie in smoke. [/] And they have the IRA dissidents [/] And these attacks in London [/] But the TV films/shows the LRA [/] And Uganda collapsing.

Although focused on individual artists in competition with one another, the slam scene has a collective spirit that has been embodied in practice in the festival, bringing together artists in conversation and refocusing the scene within Chad. N’Djam S’Enflamme en Slam has seen Croquemort collaborate with several other Chadian artists, including innovative music producer Preston, who pushed an album for him, Apprenons à les Comprendre, in his N’Djamena studio. In 2020 when Abgué Boukar Christophe wrote an article on Bokal: the little soldier of sound and image for issue No. 164 ofLe Pays, he described an up and coming musician, Gabriel Kada, stage name Bokal, who worked with Croquemort and other slam artists to add live Chadian music to their spoken words. Still current on the scene, Bokal’s latest is available under his stage name on Apple Music. The innovations in the performances don’t end there, making use of lots of light effects as well as sound — see video footage of competitions, often dazzled with multicolour visuals — with people inspired to come together to organise slam shows in less formal settings, also continuing a bottom-up approach to improving community outreach.

Issue No. 164 from July 28 to August 4, 2020

In 2018, it was N’Djamena that hosted the first Africa Cup of Slam Poetry / Coupe d’Afrique de Slam Poésie (CASP, Facebook), a Pan-Africanist event with contestants from 20 countries. And since, with the development of technology and social media reach in West and Central Africa, slam in Chad has only grown stronger, mediatised around the world. Many slam artists connect in groups over WhatsApp and Instagram, and the majority of short clips from their performances circulate in Facebook groups, breaking into newer audiences and platforms of global reach.

Reviving women’s storytelling

With its star of the international slam festival scene rising, in 2019, N’Djam S’enflamme en Slam temporarily became Slam et Eve: le slam au feminin, devoted to the slameuses. Slam Et Eve revealed not only an international network of women slam poets in francophone Africa (see Bruijn, M. E. de, & Oudenhuijsen, L. W., 2021) but a series of shared concerns. For those of us who might think we know slam poetry – whether through active participation or its representations in pop culture, or via a history lesson of the 1980s Chicago scene – this centralising of women artists and the ambition to empower them in stark contrast to Chad’s gender equality, may seem surprising. But much of what is typically understood about the form isn’t always applicable to slam in Africa.

African slam poetry blends its urban context and its literary roots with long histories of cultural expression, at once an artistic articulation for self-empowerment and a social movement interrogating injustices. Moreover, where we might associate contemporary slam with the hip-hop and rap scenes dominated by men dropping misogynist bars, slam’s inheritance and influences on the continent can be seen to have long revolved around the participation of women. They can be drawn back to centuries-old traditions of oral art forms and performances, archived in both Arabic scripts and African languages, such as the Sunjata in the Mali Empire from the 13th century, and the Ibonia in Madagascar.

Talking to Mirjam de Bruijn and Loes Oudenhuijsen in 2021, Congolese slameuse Mariusca, a.k.a. Mariusca Moukengue, also credits slam to “the language of the griots”, praise-singers and storytellers from West Africa who were typically women. Other researchers such as S.A Aliyu have also studied the African tradition of female storytellers in Hausa Women as Oral Storytellers in Northern Nigeria (1997) — a culture which, according to Daily Trust’s radiocarbon dating, may have existed for 8000-8500 years. More research on northern Nigerian female storytellers include the Tamacheq society in the Sahara who took on the roles as guardians of poetry — see Susan J. Rasmussen’s work in Gendered Discourses and Mediated Modernities: Urban and Rural Performances of Tuareg Smith Women (2003).

Cutting words

Adam tu t’es cru le plus valeureux et le plus fort, n’est-ce pas?

from ‘Adam et Eve’ by Amee

Mais la “Eve” que tu as crue faible est en train de t’emboîter le pas

Adam, you thought you were the bravest and strongest, didn’t you?

But the “Eve” that you thought weak is now following suit

In Chad, nearly one third of women experience physical or sexual violence in their lives, and 7% of girls under 14 have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM). 2023 statistics have demonstrated that FGM causes more deaths than infections from contaminated food or water, respiratory infections, and malaria in the African countries where it continues to be practised. And while the Reproductive Health Law in Chad, which seeks to prohibit FGM, among other protections for women, was passed in 2002, to date, it lacks the president’s signature required for full ratification and implementation.

Despite the psychological and health implications of FGM, one poll by the FGM/C Research Institute suggests over 50% of Chadian women aged 15-49 did not think FGM should end, with almost 47% of the same group having themselves been cut between the ages of 5-9. In some cases, young girls undergo superficial infibulation, where the vulva is sewn so that there is only a small space for urine and menstrual fluids to leave the body. The study also demonstrates that, of these women, unusually, those that live in urban areas are more likely to undergo FGM with prevalence in the capital, N’Djamena, at 37.6% of women.

Women’s slam in Chad is urban and urgent simultaneously. In 2020, it was Fanny’s, along with fellow performer and slam artist Mahmat Traoré, who founded The Chadian League for Women’s Rights, which helps victims of sexual violence receive medical and legal aid. Talking about the legal parameters with Fanny’s, she says that although “FGM is condemnable according to the legislation… we see that it still exists in our villages because of our customs and we are raising awareness around this to put an end to these practices. A woman is a human who deserves respect…the laws are there but it is the application which remains a real problem and leads to impunity.”

Uncensored / refusing the censor

Fanny’s tells me, “My journey is a testament to resilience and hope. Every day, I strive to bring about positive change and create an environment where every woman can feel safe, respected, and free to choose her own destiny. I am convinced that, together, we can build a better future, free from violence and discrimination.”

But the stakes of speaking out in slam in Chad are high and they appear to be on the rise. Fanny’s has spoken about her activism causing “so many problems with the authorities […who] do not want me to say [blunt] things.”

According to Croquemort’s interview with The Economist in 2024, autocratic coups are clamping down on Chad, especially since Mahamat Idriss Déby took power in 2021. Croquemort, the leading light with fingers on the originating pulse of the anti-authoritarian slam movement, no longer lives in Chad, having fled to the Netherlands after a “door-to- door hunt.” Financial supporters of slam festivals are pressured to withdraw, event permits are denied, radios refuse to play slam artists, and government officials appear at events with restricted topics lists. In 2014, Mirjam de Bruijn of Leiden University made clear that the former Minister of Culture has assured foreign researchers that the Chadian government “will let them [slammers] do [as they want to…] as long as they do not become too influential.” Now over a decade later, after many attempts to suppress the slammers, we wonder how much has changed in Chad for free speech, political activism, and the influence of slammers who refuse to be silenced.

Because the weather in Chad is only getting hotter and women are burning up. In the country acknowledged as the worst performer in closing the gender gap in sub-Saharan Africa (as of September 2023), where autocratic powers beat a path back from critical dissent, women are still getting on stage to speak out, and in “very, very vulgar” poetry.

In that same interview with Croquemort, Fanny’s D’Or told The Economist the promises she makes to the abusive men she encounters: “If one day life allows me, with my vagina I will piss on your face. Yes, with my pussy I will piss on your face.” In our personal conversation, I asked Fanny’s about the daily death threats she receives, the men on motorcycles who follow her home after shows, but she still dismisses them with a speed that makes me wonder how many times she has already repeated this: “Men don’t scare me because it’s a noble fight for me and mentalities must change.”

Yet when, in her piece ‘Clitoris’ that Fanny’s performed for me, she calls on her muse, “Cher culturiste, au creux des nuits sans fin” (excerpted above), the language is tenderly sophisticated, whimsical, and interlaced with multiple meanings.

‘Culturiste’, literally bodybuilder, can be a metaphor for the womb, something or someone tending to a physical body, in the way, perhaps, of a sculpture artist. Likewise, ‘creux’ has double meanings, translated above as ‘folds’, but also holding meaning as a delicate way of describing the site where something might nestle itself, like in a burrowed hole behind the folds.

Many people know of the violence inflicted by FGM, but as Ivorian slameuse Amee (a.k.a. Aminata Bamba) expressed in 2021 in an interview with Loes Oudenhuijsen, “If we don’t speak about it, it doesn’t exist…when we speak, when we say something, we bring something to light […] I slam to bring things into existence.” In 2017 in an interview with Leo Pajon for JeuneAfrique, slameuse Malika Ouattara claimed there were only around fifteen African slameuses. But, Fanny’s tells me that “today there are a few more in Francophone Africa who are doing a very good job.” As the elder slam sisters pave the way for the next generations, they find their own voice and sophistication to use it with strength, with song, tremors, and often tears, shared by girls and women alike.

In our conversation, Fanny’s, speaking with all those slameuses joining the throng, tells us what some of us already know: “We don’t have to be muzzled all the time.”

Fanny’s D’Or is Épiphanie Dionrang, Chad’s number one slameuse and President of the Chadian League for Women’s Rights. After a close friend was tragically kidnapped, raped, and murdered, Épiphanie’s career became marked by an urgent need to defend women’s rights. She has initiated national and international advocacy efforts to empower women and girls, including organising the first peaceful women’s march in protest to the impunity of gender-based violence perpetrators in 2025. She is also the project founder of INKHAZ since 2020, a health platform meaning ‘rescue’ that raises awareness of the seriousness of gender-based violence, demanding justice while providing a space of solidarity, collective advocacy, and resources for survivors who are often ignored. Épiphanie’s mission is marked by a determination to break the silence and to change attitudes around gender-based violence. By connecting with survivors, she aims to help them understand that despite the trauma they have suffered, they can still find their way back to happiness and decide their own future.

Leonie B Predić is an undergrad reading Comparative Literature at King’s College London. At King’s, she was the first Communications Officer in the new World Literature Society, and is currently researching forms of colonial and post-colonial imperialism in European poetry for a dissertation on William Blake. Leonie writes poetry, fiction, and non-fiction essays that blend academic analytical thought with creative interpretations, cutting across media forms, historical moments, and places, on the ‘Leonie in The World’ Substack.

With special thanks to the team at Africa in Words, including Katie Reid, for extra valuable insights, Lydia Metaxa for her generosity with translations, and above all, Fanny’s D’Or for her empathy and bravery.

Categories: Reviews & Spotlights on...

Spotlight on… Step back and step aside: Rereading Caroline Rooney on animism and African literature, a quarter of a century later

Spotlight on… Step back and step aside: Rereading Caroline Rooney on animism and African literature, a quarter of a century later  Q&A: Spotlight Interview with Ellah Wakatama, Chair of the Caine Prize for African Writing

Q&A: Spotlight Interview with Ellah Wakatama, Chair of the Caine Prize for African Writing  Review: Nadia Davids’ ‘Bridling’ (on the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024)

Review: Nadia Davids’ ‘Bridling’ (on the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024)  Review: Home as Relationship – Tryphena L. Yeboah’s ‘The Dishwashing Women’ (on the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024)

Review: Home as Relationship – Tryphena L. Yeboah’s ‘The Dishwashing Women’ (on the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024)

join the discussion: