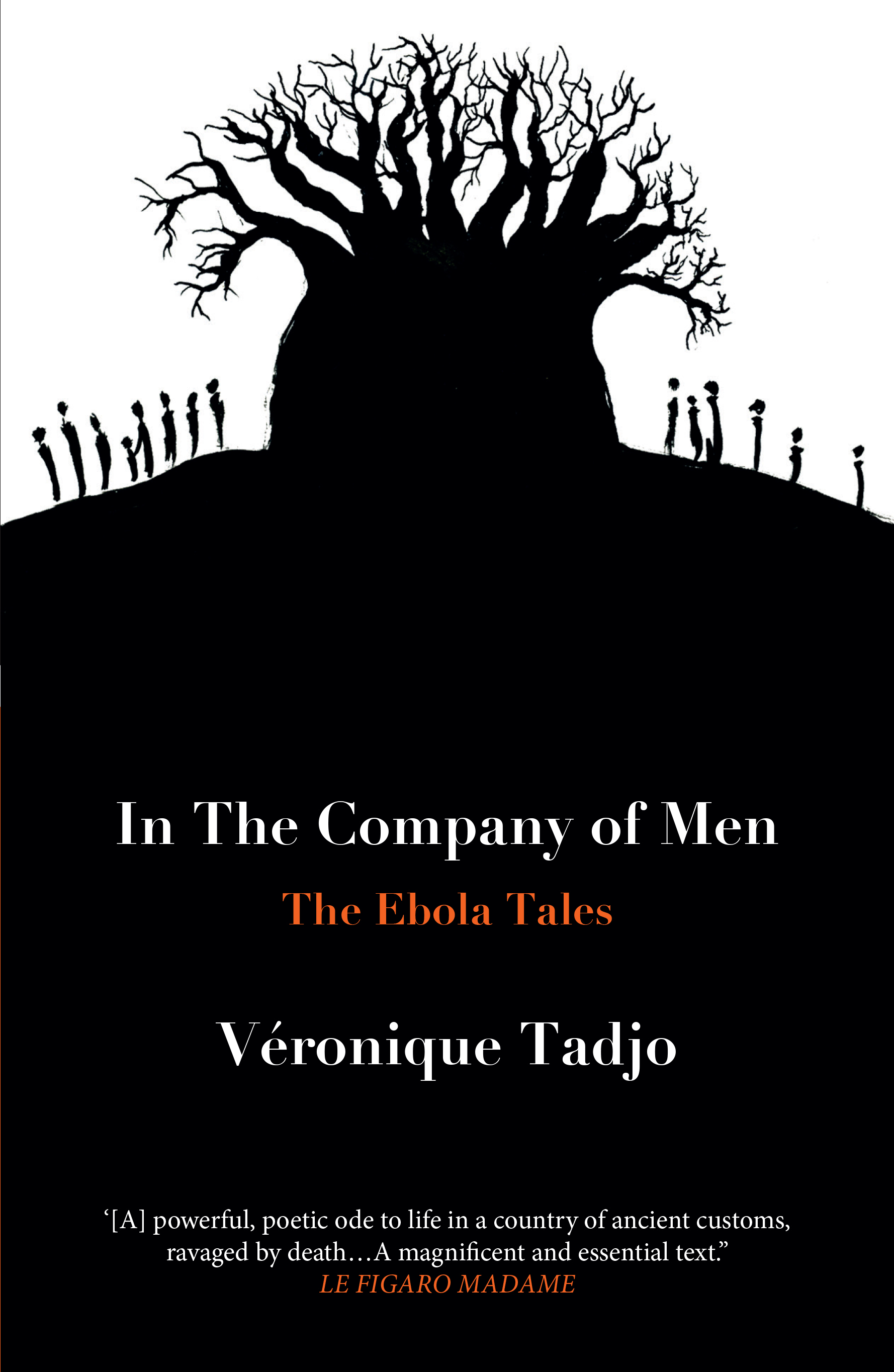

AiW note: Véronique Tadjo is a writer and painter from Ivory Coast. This year marks the release of her latest novel in translation, In the Company of Men: the Ebola Tales (with HopeRoad Publishing, first pub. En Compagnie des Hommes, 2017), which draws on real accounts of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa of 2014 to weave a moving and reflective fable on “both the strength and the fragility of life and humanity’s place in the world”, acutely relevant to our times.

AiW note: Véronique Tadjo is a writer and painter from Ivory Coast. This year marks the release of her latest novel in translation, In the Company of Men: the Ebola Tales (with HopeRoad Publishing, first pub. En Compagnie des Hommes, 2017), which draws on real accounts of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa of 2014 to weave a moving and reflective fable on “both the strength and the fragility of life and humanity’s place in the world”, acutely relevant to our times.

Last week, ahead of her review here, we published a Q&A with Tadjo – On opening up new possibilities with In the Company of Men – in which AiW Editor Davina Philomena Kawuma caught up with Tadjo by email, discussing the book, its translation and its poetry, being an academic and a fiction and poetry writer, as well as writing for children and YA, and the significance of solidarities in times of pandemics and crises. This review accompanies the Q&A in its ongoing conversation and engagement with the novel and the co-generative strands of Tadjo’s work.

![]()

My siblings and I were raised by a father who spoke bluntly about death, often offering detailed instructions about what to do if he died before our mother, most of which could be condensed into “take care of your mother, and of each other.” No matter how many times our mother tried to intervene with the Luganda version of “Darling, you’re frightening the children,” he would not be deterred.

Consequently, for a long time, I told myself that I had an uncomplicated relationship with death, and so with mortality. Then the Covid-19 pandemic struck, and “uncomplicated” no longer seemed like a realistic word.

At the height of the pandemic – miles away from home, drifting in and out of bouts of anxiety, watching for the re-opening of airports – I worried the meaning of belonging, and of the rights and duties of “community”: the country I’d called home for my entire life wouldn’t admit me for fear that I might infect it with Covid-19.

Amidst bombardment of news of rising death tolls, summarily executed disposals of the dead, and mismanagement of Covid-19 relief funds, I was filled with thoughts about why it must take death to put things into proper perspective, sympathy for those that weren’t able to bury their loved ones in accordance with religious and cultural rituals that lessen grief, and astonishment at the breadth and depth of human greed.

The 2021 release of Véronique Tadjo’s In the Company of Men, translated into English by Tadjo with John Cullen, deliberates similar anxieties and bewilderments. Intensively researched in both French and English, Tadjo employs an unpretentious style and accessible language to the devastation of the 2014 Ebola outbreak across West Africa. The novel successfully complicates several issues that are pertinent, not just to our current crises of the pandemic and its management, but more broadly to modern life, including the contradictions intrinsic to more popular ideas of progress, destructive patterns of human behaviour, and patronizing attitudes towards non-human lives.

In the Company of Men is set in and around an unnamed village, the anonymous “everyplace” of its natural beauty being destroyed by the scramble for raw resources, here in the shape of gold. The 16 sections into which the narrative is divided chart a dramatic course of desertion, silences, and vigilance through a broad cast of human and non-human characters, some shriller than others.

The human characters include the young hunters who unwittingly bring death to the village by eating wild bats, the medical teams that arrive to disinfect the scenes and bury the dead, a dying mother, a lover who wants the poems addressed to their fiancée to read like screams aimed at the sky, the public health officials that threaten to strike for higher pay, and the local and foreign governments (and non-governmental bodies) that rally financial resources and speak the languages of battle and victory in relation to the virus.

As each of these voices and their related “languages” intertwine across the narrative’s sections, they share the burden and consequences of the outbreak as it affects their own life cycles: from limitations imposed by heavy protective clothing on touch, speech, and active involvement in the lives of loved ones, to long-lasting physical and emotional wounds represented by frequent encounters with disembodied souls and echoed by deep survivor’s guilt.

The non-human characters – which include the Ebola virus, and the bats and trees that inhabit the forest at the edge of the village – are as idiosyncratic as the humans.

The Ebola virus has a favourite song – Zao’s Ancien combatant, which “illustrates what’s so grotesque about Man and his incurable, pathological destructiveness,” – as well as a sneering disbelief of humanity’s capacity for self-awareness, to say nothing of the kind of unity that’ll outlive our greed:

… if Man could only acknowledge his dark side as an intrinsic part of his being, he’d surely get better at keeping his destructive instincts under control, instead of letting himself be controlled by them. Humans should just step back, examine themselves dispassionately, and look for effective ways of ending the carnage. They should forget their absurd ideas about brotherhood and solidarity, which they shamelessly flout anyway, and become more realistic. (118)

And the bat, immensely proud of its bird-mammal hybridity, of having both a bright and dark side, feels unfairly implicated:

Is it my fault if Ebola has left my belly and is now spreading panic among humans and animals? What was I supposed to do about that? I thought we had an agreement and that it was content with that. But look at me now – I’m the one that gets demonised. (122)

The trees, which consider themselves clear-sighted custodians of the earth’s resources, are alert to the risk that human greed poses, why the persistent sorrow in and around the village is about much more than “bad luck,” and the ways in which our destructiveness forces animals, some of which may be carriers of highly infectious zoonoses, to seek our company:

You cannot destroy the forest without spilling blood. Humans today think they can do whatever they like. They fancy themselves as masters, as architects of nature. They think they alone are the legitimate inhabitants of the planet, whereas millions of other species have populated it since time immemorial. Blind to the suffering they cause, they are mute when faced with their own indifference. Their voracity is boundless; it seems impossible to stop them. The more they have – and they already have everything – the more they devour. (10)

It is the trees that are better-placed to articulate (and contextualize) the grief caused by the loss of so many human lives in such a short time – grief that’s intensified by new, formal rules of burial, which seem beyond the ordinary understanding of the villagers but which international health and safety protocols demand.

And it is the Baobab tree, custodian of centuries-old memories, with a crown that penetrates the sky and roots that plunge into the earth’s womb, that is the ultimate symbol of the connection between the past and present, and between humanity and nature. Free from the usual fears or doubts about death, the Baobab tree is simultaneously able to caution against activities that break the chains of existence, address our reluctance to speak often (and informally) of death, and defend humanity against Ebola (the character) and its chilly cynicism.

By upholding confidence in humanity’s ability for self-reflection and unity, the Baobab tree keeps hope afloat in a way that encourages us to come to terms with our mortality, and to form the kind of covenants with nature that will protect the earth and its resources from the excesses (and blind spots) of the Anthropocene, evoking the depth of the trouble it should be causing to the many, not the few, as Heather Anne Swanson reminds us (‘The Banality of the Anthropocene’).

At a time when more than mere superstition makes it unseemly to speak of death before death is due, In the Company of Men is an invitation to a particular kind of preparedness — even to gentle ways of “frightening the children”, in my mother’s words — if only so that we might re-evaluate the status that humanity has assigned to itself. By listening to the many, as the book’s non-didactic and delicately wrought world amplifies, we begin to resist the temptation to assess reality only in terms of human knowledge and values, thereby creating spaces that privilege multiple perspectives and collective responsibility. This offer, a form of solidarity as accountability, is an invitation which I wholeheartedly accept, and which I hope we all can, too.

See Davina Philomena Kawuma’s accompanying AiW Q&A with Tadjo here.

![]()

Categories: Reviews & Spotlights on...

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’  Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)

Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

join the discussion: