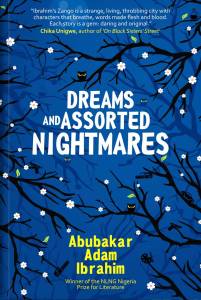

AiW note: Dreams and Assorted Nightmares is Ibrahim’s third book and second story collection, newly released with Masobe Books. In the interview below, Umezurike and Ibrahim discuss the interconnecting fantastical short stories of the collection, their exploration of the “spaces between life and death and beyond”, and the compelling “spectre” or character, even, of setting and place, in the context of Ibrahim’s other writing and influences…

Umezurike: Congrats on your latest short story collection Dreams and Assorted Nightmares, which is a fascinating read. I like that it is full of the grotesque, the fabulous, and the mythical. The characters are exciting, even in their flaws and misadventures. This book is markedly different from many of the stories in The Whispering Trees. Are there particular reasons why you have chosen to write stories about the bizarre and preternatural?

Umezurike: Congrats on your latest short story collection Dreams and Assorted Nightmares, which is a fascinating read. I like that it is full of the grotesque, the fabulous, and the mythical. The characters are exciting, even in their flaws and misadventures. This book is markedly different from many of the stories in The Whispering Trees. Are there particular reasons why you have chosen to write stories about the bizarre and preternatural?

Ibrahim: Thank you, Uche. I had fun writing the characters in this collection and I hope that readers will have fun reading them. Are these stories markedly different from The Whispering Trees? They incorporate many of the elements found in The Whispering Trees and perhaps push the envelope a bit. The reason is that Zango, where the stories are set, is a character in these stories in a way. It has a hold on every single person born in it. But Zango also existed in The Whispering Trees. It is that place called Mazade in the story “Cry of The Witch,” in which a plague wiped out the entire population of the town. Zango is the reincarnation of Mazade in this century, in this present. It is the same place in a different time with different characters and this time I let myself linger in this place. It has the idiosyncrasies of Mazade and more. It is a bizarre space. It is a fantastical space. It is mythical and magical because it is a reflection of Nigeria where the improbable is often the norm, in the physical, political and the mythical space.

Umezurike: How did Dreams and Assorted Nightmares come together? When did you first get the idea for the book?

Ibrahim: I actually can’t remember what I was doing when the idea struck me. But I have always been fascinated by the idea of space as a character and space in terms of the hold it has on the people who inhabit it. I am intrigued by how a space develops a culture, which the people in it imbibe without ever meeting each other. Zango’s hold on the people born in it is far more immersive and invasive. Their lives are tied to the place even if they don’t know it. The idea started as this random place where random people gather on their way to somewhere else. Once this space took shape in my mind, it was easy to people it with character and their stories. So in essence, the idea of the collection was to create a profile of the lives of some of the people who inhabit Zango and how their actions and decisions, completely random, completely independent of each other, pool into a collective force that triggers something that will affect the whole. I suppose this is something that comes out of living in Nigeria, where the stupidity of some random person in Kano or Aba, for instance, will have dire consequences for the lives of persons living on the opposite side of the country.

Umezurike: While reading your collection, I recalled another fantastic collection The Prophet of Zongo Street by Mohammed Naseehu Ali. Why do you choose to place your stories in Zango?

Ibrahim: I have never heard of this book before. But it is an irony considering there is a man who could pass as a prophet in Zango – he could be called the prophet of Zango, in a way. When I wrote the first story, it wasn’t always called Zango. It was called something else that connotes a transient space, a station, if you like, where people stop before getting to their destination. But eventually it grew, became home and over the years lay claim to all the children born in it. Creating this space for the stories is an exploration of the hold a place like Nigeria has on its people. This fantastical weird, endlessly infuriating place full of drama, the mundane and the extraordinary. Zango itself is a Hausa word for a resting place, or a stopover. Somewhere that is not supposed to be permanent, it is an in-between place. The original inhabitants of Zango were people who were travelling to somewhere else and decided to stop over at Zango to rest. But the space took a hold on them and it became home. So Zango is also about the transience of things and the sense of impermanence of life, of love of resentment and hate and all the notions we hold so dear to us that in a few years, when we look back, seem to lose all relevance.

Umezurike: I am just wondering why you chose a short story cycle over a novel, considering that the stories are interrelated and interweave into each other?

Ibrahim: I felt that was the best way to examine the influence of the town in the lives of each of the characters, how invariably different their lives are and yet how intimately connected they are. For some time, I have been interested in this type of storytelling because I am really interested in the interconnectedness of destinies and fates, how a person arriving late or on time could have a huge impact on the lives of some totally random stranger, or other such coincidences. I think this sort of storytelling idea for me was inspired by VS Naipaul’s Miguel Street, which I read a long time ago. I am also curious about exploring this form in a novel and maybe someday I will. The idea is there. I just need to sit down and write it.

Umezurike: Could you say a few words about how long Dreams and Assorted Nightmares took you to complete?

Ibrahim: Again, I really can’t say. Dreams and Assorted Nightmares wasn’t a burst of writing. It was something I did in between other writing projects. It was the space I went to and gave myself permission to be wild. What I know for sure was that I finished working on it in 2018 and I put it away and moved on to other things.

Umezurike: I have always found your writing to be poetic. Your novel Season of Crimson Blossoms is replete with beautiful poetic language and imagery. Which poets do you read?

Ibrahim: Thank you, Uche. This coming from a poet of your calibre is a great compliment. My relationship to poetry has always been complex. I was in the science classes in secondary school even though I loved literature and would actually go on to teach it at some point. But I have always had this touch-and-go relationship with poetry, how self-absorbed it is sometimes at the detriment of the reader. I suppose this has affected my consumption of poetry and still does. Even when I write poetry, some of which have been published in anthologies, I hardly call myself a poet. Something in me has not given me permission to deploy that word on myself. I just think of myself as someone who is enchanted by words and their usage in terms of deconstructing and remaking reality. But I have enjoyed the poetry of Rumi, Hafez, Neruda, Gibran and even Edward Hirsch. I have also been delighted by the works of poets, like yourself, Uche Peter Umez, Umar Abubakar Sidi, Richard Ali, Ismaila Bala and Warsan Shire. There are younger poets like Romeo Oriogun, Saddiq Dzukogi and David Ishaya Osu, who are doing fascinating things with the genre as well.

Umezurike: The ending of Dreams and Assorted Nightmares is beautifully wrought. I like how Zaki didn’t seem concerned about the consequences of his action; instead, he looked poised crunching nuts. Can you speak briefly about why you ended the story on that scene between Zaki and Bello?

Ibrahim: I wanted to capture how Zaki is very aware of the possible consequence of his action yet seems completely unperturbed by it, just as someone in Nigeria who goes to vandalize a public property, say a transformer, which could be sustaining someone’s life at that moment but is completely unconcerned by the consequence of his action. Zaki is not just a vandal; he has always been a curious character, as we see in the very first story where he is casually mentioned. But by that final scene we know who he is, his motivation, we see how hurt he is, how he feels rejected by Zango and having known the things he does at that point, felt his action at that point is a fair thing for him to do. Basically, it is my way of encapsulating the attitude we have when we rip out power cords that service an entire community for profit, or how we sabotage ourselves consistently in our journey to nationhood.

Umezurike: Which other novelists aside from Gabriel García Márquez have influenced your writing of late? Why?

Ibrahim: Every writer I read influences me in some way, either through how much I enjoy the book or how much I don’t. In terms of my reading lately, this has been a most unfortunate year. I have read books that have elicited in me the deepest sense of outrage. I have read a few good ones too. Those are my salvation this year. I fear my influences are fully formed though. I have been writing this way, for a long time, even before I met Marquez as a reader. What Marquez did for me was to give me the validation to continue writing the way I write and I think for a writer on the periphery of different forms of writing, that is important. I enjoy writing that threads these margins, so in that sense I have enjoyed the works of Ondjaki, Jose Eduardo Agualusa. Maaza Mengiste, too, has been a highlight of late. I have also been intrigued by Samantha Schweblin’s Mouthful of Birds.

Umezurike: I know you are working on a novel, and how is that coming along?

Ibrahim: The novel is finished. At least for now. For the writer, is a book ever finished if it is not taken off his hands and published? The desire to go back and tweak something is always there. But for now the novel is finished and I have given myself permission to put my feet up and catch my breath for the rest of the year at least.

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim is a Nigerian creative writer and journalist. His debut short-story collection The Whispering Trees was longlisted for the inaugural Etisalat Prize for Literature in 2014, with the title story shortlisted for the Caine Prize for African Writing – read our Caine Prize blog review (2013) here. Ibrahim won the BBC African Performance Prize and the ANA Plateau/Amatu Braide Prize for Prose. In 2014, he was selected for the Africa39 list of writers aged under 40 with potential and talent to define future trends in African literature. His first novel, Season of Crimson Blossoms, won the Nigerian Prize for Literature, Africa’s largest literary prize in 2016.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD Candidate and Vanier Scholar in the English and Film Studies department of the University of Alberta, Canada. His critical writing has appeared in Tydskrif vir Letterkunde, Postcolonial Text, Journal of African Cultural Studies, Cultural Studies, Journal of African Literature Association, and African Literature Today. He is a co-editor of Wreaths for Wayfarers, an anthology of poems.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD Candidate and Vanier Scholar in the English and Film Studies department of the University of Alberta, Canada. His critical writing has appeared in Tydskrif vir Letterkunde, Postcolonial Text, Journal of African Cultural Studies, Cultural Studies, Journal of African Literature Association, and African Literature Today. He is a co-editor of Wreaths for Wayfarers, an anthology of poems.

Umezurike has been a long-time generous contributor to AiW. For more of his AiW posts, including his Words on the Times – a Q&A set intended to connect our communities up during the challenges of the pandemic – please click through to his AiW Guest posts here.

Categories: Conversations with - interview, dialogue, Q&A

Q&A: Koleka Putuma -Revolutionising the archive and (backspace) dancing… ‘Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come in’

Q&A: Koleka Putuma -Revolutionising the archive and (backspace) dancing… ‘Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come in’  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Q&A: Publishing roundtable – #ReadingAfricaWeek

Q&A: Publishing roundtable – #ReadingAfricaWeek  Q&A: Words on… e-Kitabu – the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair

Q&A: Words on… e-Kitabu – the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair

join the discussion: