AiW Guest: Sana Goyal.

It’s the Saturday afternoon of the Africa Writes weekend in London — the 2018 edition. Sitting in the second row of the Auditorium at the British Library, I hear several excitable voices over my shoulder. And as I eavesdrop, I smile to myself. ‘Oh no, the UK edition [Faber & Faber] isn’t officially out until November,’ says one voice. ‘But they’re selling a few, limited copies outside, as part of the pre-launch,’ she adds. (I make a mental note to rush out to purchase a copy when the event is on the precipice of ending.) ‘I ordered this, the American one [Grove Atlantic], online, when it first came out,’ says another. The women then proceeded to compare book covers, deciding, ultimately, that both were beautiful in their own ways, and worth their wallets and place on their bookshelves. If Akwaeke Emezi was the talk of the literary town, one thing was certain: Freshwater, perhaps the most anticipated African literature debut of the decade, was its must-have bookish accessory. You wanted to be seen clutching a copy, you wanted to gather around in circles and discuss plot details (or fall short of words to describe the reading experience) — you wanted to be part of the crowd that had read it, so you could claim to never have read anything like it, not even close.

It’s the Saturday afternoon of the Africa Writes weekend in London — the 2018 edition. Sitting in the second row of the Auditorium at the British Library, I hear several excitable voices over my shoulder. And as I eavesdrop, I smile to myself. ‘Oh no, the UK edition [Faber & Faber] isn’t officially out until November,’ says one voice. ‘But they’re selling a few, limited copies outside, as part of the pre-launch,’ she adds. (I make a mental note to rush out to purchase a copy when the event is on the precipice of ending.) ‘I ordered this, the American one [Grove Atlantic], online, when it first came out,’ says another. The women then proceeded to compare book covers, deciding, ultimately, that both were beautiful in their own ways, and worth their wallets and place on their bookshelves. If Akwaeke Emezi was the talk of the literary town, one thing was certain: Freshwater, perhaps the most anticipated African literature debut of the decade, was its must-have bookish accessory. You wanted to be seen clutching a copy, you wanted to gather around in circles and discuss plot details (or fall short of words to describe the reading experience) — you wanted to be part of the crowd that had read it, so you could claim to never have read anything like it, not even close.

Emezi, an Igbo and Tamil writer and artist, born in Nigeria and “based in liminal spaces”, has the 2015 Miles Morland Writing Scholarship and the 2017 Commonwealth Short Story Prize for Africa, publications in Granta and The Cut, and early praise from Taiye Selasi, Chinelo Okparanta, and NoViolet Bulawayo for Freshwater, to their name. Edwidge Danticat, writing in The New Yorker, described the debut as “an extraordinarily powerful and very different kind of physical and psychological migration story” — and Freshwater’s release was received with rave reviews. Rather unsurprisingly, then, it is already on a handful of prize long lists, and has found its publishing home in Nigeria with one of its leading independent publishers, Farafina Books, whose authors include fresh voices such as Lesley Nneka Arimah, Yewande Omotoso, among others. Emezi’s first YA novel, Pet, will be published in the US in 2019 (Make Me A World, an imprint under Alfred A. Knopf) — and the author recently revealed a two-book deal with Riverhead Books, where their second adult novel, The Death of Vivek Oji, will be published next. Emezi also has close to 30K Instagram followers, a platform they use for video art and “self-portraits”. In a high-profile author shoot, the likes of which we’ve perhaps come to associate with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Emezi featured alongside their photographer sister (Yagazie Emezi) in US Vogue‘s February issue — and photographed by Annie Leibovitz no less.

All of this meant that, at 15.45, when Akwaeke Emezi walked onto the Africa Writes stage at the British Library in London, led by Irenosen Okojie, panel chair and the Betty Trask award-winning author of Butterfly Fish (Jacaranda) —and to loud applause — the audience, murmuring animatedly until then, fell to a mum. There was a shared sense of knowledge that the words said and shared in the forty-five minutes to follow promised travel into other worlds, far beyond fiction.

Africa Writes. Image credit Elizabeth Wirija.

Emezi began with a triptych of carefully curated readings, which, together, gave a sense of the autobiographical novel’s multiplicity of selves/voices as a whole. A meditation on the metaphysics and mysteries of identity and being, Freshwater features Ada, the novel’s protagonist and multiply plural spirit — born “with one foot on the other side” — and a lifetime of traversing thresholds… Here Emezi’s phone buzzes — “interrupted by a whole author” they say — charmingly deflecting the embarrassment of the moment by casually referencing their own sense of self, with a humour not lost on the Africa Writes audience, who clap and cheer Emezi on.

Okojie’s opening observation — and question — is about the book’s fluidity between different dimensions and planes, and the ways this offers a distinctive aesthetic. ‘It almost feels like you’re stretching perspective,’ she says.

‘That question is always interesting for me, because I feel like I should have a deep literary answer for it. But the truth is that it’s an autobiographical novel — and I wrote it that way because that’s the way it was. I tried to think about it as this progression from fractured selves and moving over to thinking of it as just multiple selves. I wanted to set this book in what the actual lived experience was, which was of being multiple. And it could have been written from what’s known as the outside, where it would’ve just looked at the Ada, and would’ve looked like one,’ Emezi explains.

‘But there’s a Toni Morrison quote that I overuse, and I say it all the time: “I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central. Claimed it as central, and let the rest of the world move over to where I was”. With Freshwater, that’s what I wanted to do. I was like, let me put the story inside — like inside this experience that is multiple, and non-linear, and that is confusing — and this is the closest way to get the reader to experience what it felt like.’

The Bluest Eye first edition cover (1970)

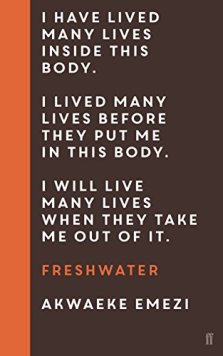

Interestingly, taking the same para-textual path and intimating a similar literary lineage, the jacket design for Freshwater’s UK edition was originally modelled on the first edition of Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, which put the first page of the novel on its cover.

@azemezi on the pre-Africa Writes pre-launch Faber cover

With Emezi’s own, they tweeted, they used Freshwater’s epigraph: “I have lived many lives inside this body. I lived many lives before they put me inside this body. I will live many lives when they take me out of it”.

Emezi then revealed why it was so important for them to centre the book in Igbo ontology, and the power in self-naming: ‘In doing this work, there was a shift I had to make in myself. This is real, I told myself — let’s just start from that premise. It’s not juju, it’s not superstition, it’s not magical realism, it’s not speculative fiction — it is just real.’ Emezi has explained elsewhere, in the article on The Cut, that Ogbanje is “an Igbo spirit that’s born into a human body, a kind of malevolent trickster” — and has also written about how Freshwater is a book rooted in certain autobiographical “realities”, most significantly their own “identity… as an ogbanje”.

‘I had started working with the ogbanje premise way before I started writing Freshwater’, they said, back at Africa Writes. ‘I had been making paintings about wanting to go home, and not understanding what that was — because home did not really exist in this realm. I used a lot of journals whilst writing Freshwater, and I have entries dating as far back as when I was 16, and in Nigeria: “I want to go home, I want to go home, I want to go home,” they said. ‘But I was at home! What home are you talking about?’ In writing Freshwater, then, Emezi found the hitherto elusive and longed-for home.

Part of the reason Emezi requested for the book to be categorised as an “autobiographical novel” (not a mere marketing ploy) was because ‘if you put it as fiction it lends to the view that it’s just fiction — it’s make-believe, these realities aren’t real’. And ultimately, the book is about a metaphysical subject whose main problem is embodiment, and who is not coping with it very well, they added. What was Emezi’s approach to the form, to writing the book’s poly-vocal perspectives? ‘I had no map, but I knew the skeleton, what chronological order it goes in — because it’s based on the archive of my life’.

I read Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater in the immediate aftermath of their launch event at Africa Writes, and in three large, greedy gulps. In the midst of London’s heatwave, it quenched a reading thirst I didn’t know I had in me. That’s when I realised: Freshwater isn’t just a bookish accessory you flaunt, it’s a gift you keep close.

![]()

instagram.com/azemezi/

For stockists, sales and reviews see Freshwater at Emezi’s website:

www.akwaeke.com/freshwater

@azemezi | https://www.instagram.com/azemezi/ | https://www.facebook.com/azemezi

![]()

Sana Goyal is a PhD candidate at SOAS, University of London. Her research lies at the intersection of contemporary African literature in English, literary prizes, and women writers. When she’s not thesis writing, she works as a freelance book critic for Vogue India, Mint Lounge, India, and Scroll.in. She’s also the Reviews Editor of the third issue of CHASE’s Brief Encounters journal. She’s at home in Mumbai and London.

Sana Goyal is a PhD candidate at SOAS, University of London. Her research lies at the intersection of contemporary African literature in English, literary prizes, and women writers. When she’s not thesis writing, she works as a freelance book critic for Vogue India, Mint Lounge, India, and Scroll.in. She’s also the Reviews Editor of the third issue of CHASE’s Brief Encounters journal. She’s at home in Mumbai and London.

![]()

This is the second in a series of posts following up the 2018 Africa Writes Festival at the British Library in London. Read the first, ‘Building an Archive – Voices from the Panel “Loving Womxn: Deliberate and Afraid of Nothing”‘ by our regular AiW Guest, Kasia Kubin.

AiW also partnered with Africa Writes this year to host a Literary Podcasts panel, ‘Books in your Ears’ , a conversation with the voices and producers behind Not Another Book Podcast, BakwaCast and No Bindings – with video interventions into the discussion from 2 Girls & A Pod – on the growth in podcasts for, on, and about African literature. You can read the first of our posts on literary podcasts, by AMLA Network Convener Gaamangwe Joy Mogami, who shared with us her take on these new spaces of literary discussion and her top 5 recommended listens. Watch this space for our podcasts, panel and event reviews after Africa Writes soon to be publishing on AiW.

Categories: Reviews & Spotlights on...

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’  Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)

Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

join the discussion: