Ank ara Press is a new romance imprint published by Nigerian publishing house Cassava Republic Press. The imprint launched on 15th December 2014 with six new titles, set in locations in Nigeria, South Africa and the UK. AiW author Emma Shercliff and publisher Bibi Bakare-Yusuf discuss the process of creating romance for the African market.

ara Press is a new romance imprint published by Nigerian publishing house Cassava Republic Press. The imprint launched on 15th December 2014 with six new titles, set in locations in Nigeria, South Africa and the UK. AiW author Emma Shercliff and publisher Bibi Bakare-Yusuf discuss the process of creating romance for the African market. ![]() ES: Bibi, could you tell me a little about the Ankara Press imprint, and specifically about how it was conceived and why you thought it was important to launch a romance list?

ES: Bibi, could you tell me a little about the Ankara Press imprint, and specifically about how it was conceived and why you thought it was important to launch a romance list?

BBY: Two reasons. Firstly, I felt that our ideas about African literature needed to be more diverse. Every time we think about African literature we think about literary fiction. We don’t think of African literature in terms of genre fiction. Yet genre fiction is the mainstay of many publishing houses all over the world. It’s curious to me why, in African publishing, genre fiction hasn’t taken off in the way that one would have imagined. There has been a history of genre fiction i.e. crime, romance, through the Pacesetter series, in the late 70s, 80s. There was also the Onitsha market literature of the 50s and 60s, the Kano Soyayya romance novels of the 80s and today. So there’s that tradition, but in terms of their symbolic positioning within the cultural landscape, we don’t think of those books as African literature. They are market literature, with its connotation of low culture. So I wanted to basically puncture that limited and limiting way of viewing African literature, through the canon established by the African Writers Series. And I was thinking that Cassava Republic was falling also into that trap. Our aim is to feed the African imagination and to do so, we need variety. The second reason has to do with my own feminist inclination and work on gender issues in Nigeria. I realise that so many women, even those who claim to be gender activists or feminists, have very patriarchal notions of femininity and masculinity, and expectations of the role of men and women in relationships. Talking to women, I realise that so many of us have these unrealistic expectations of men. Our ideas of romance seem to be very fairytale and not in tune with the reality of our lives.

ES: And so you think that one of the reasons for these constructions is because of literature or things that they may have read?

BBY: Yes, I think literature is one reason, but also music and Hollywood films, which are hugely popular in Africa, have shaped the way in which women are positioned vis-à-vis men and the dependency around that has given African women an idealised notion of relationships. I was talking to a lot of Nigerian women and realised that so many women read romance when they were growing up: Pacesetters, Mills and Boon, Harlequin, Barbara Cartland. And that completely by-passed me, I didn’t read any of them, apart from the Pacesetters series. To my mind, the consumption of these Mills and Boons with their idealised masculinity, their idealised femininity, actually can create a sense of diminishment of women, or of who women are, as you have this expectation that the man must provide and take you away, and you need a man to be fully fulfilled. But I thought, ok, what we could do is to think about how we could work within that same genre and also then subvert it. Subvert it by being deliberate about how both men and women are constructed. We all know that what it means to be a man and a woman is a set of socially learned performances and acts. So I thought why not bring this tacit mode of being into consciousness.

ES: And we’ve talked before about a commercial imperative as well, that obviously there’s the ideological reason for publishing but clearly as a commercial publisher…

ES: And we’ve talked before about a commercial imperative as well, that obviously there’s the ideological reason for publishing but clearly as a commercial publisher…

BBY: I said two reasons before, so actually there’s a third reason, which is that romance sells. So I thought, if I marry the commercial imperative with the ideological imperative we might have a winning formula. You know, a lot of people who would not ordinarily read a Cassava book might read this, and a lot of people who may not read romance might be drawn to our brand of romance. We know that the Soyayya romance novels might sell 50,000 copies, 100,000 copies. No literary fiction in English in Africa sells that kind of quantity. I also wanted to reflect some of the women I see around me, who are very strong; they want romance, they want to love, they want to be loved, they want to have passionate sex, but at the same time they are independent, they want to have fulfilling careers, they want to own their own destiny, be in control of it. They’ve all consumed romance with white heroes and heroines, so I thought, what would it be like to have romance where an African woman is at the centre of it, an African man is the love object, and that’s not to say that the women can not love men outside of their race, but rather to place African coupling at the centre, for our readers to see their lives represented in full Technicolor. I think when you do that in this culture it gives a certain cultural confidence to those who are consuming. It is one thing to be consuming Mills and Boon or Harlequin, where everybody is white and you can almost erase the colour and it’s very subtle, but when you see yourself at the centre it makes romance something that you can access yourself, it is not something that you can idealise, it’s not something over there, only for white people. You can see positive examples of sensuality and passion that show black women and men desiring and devouring each other.

ES: And at the time when you were thinking about commissioning the Ankara books, were there examples of black men and women in literature that you thought of as good models in romance literature in particular, or more broadly?

BBY: In romance no, because I didn’t really read romance fiction. However, when I was thinking about starting the imprint I happened to be in South Africa and came across Sapphire Books. I bought three Sapphire books and five Mills and Boons. I started reading, Mills and Boon first. I read half of one and I just couldn’t relate to it. I couldn’t relate to the storylines, I just wasn’t getting it. Then I started reading the Sapphire books, I remember, on a Friday; by the Saturday morning I had finished all three and went back out again to buy some more. And I started thinking about what was driving me to consume these very fast-paced books, which is really outside of my normal pattern. And I realised it was because black people were at the centre of it.

ES: You think it really was as simple as that for you?

BBY: Yeah! Because the structure in terms of the boy meets girl pretty much follows the Mills and Boon model. With Sapphire books, here is a world of black people who were making it and making out, who had really nice jobs, worked in nice magazines; this is what white women did, at least as represented in literature. I laughed thinking about it but then I thought to myself actually what happens to a lot of readers. They’re not aware how the racial discourse is working through them; we just consume popular stories in which African heroines are not the norm. We do not think about the impact these narratives might have on us, on our expectations. With Sapphire books, there were young black women and they were successful, or about to be successful, they had a career, they were pining after a guy, but not to the detriment of their own sense of self. And so Sapphire, in a way, provided an example of what I’d been thinking about. So there’s a precedent in what we are trying to do. But we needed to think about the template of how we do it.

ES: I went back to the submission guidelines that were sent to all the authors and I was struck again how formulaic they were. I mean we know that romance is a formulaic genre. But it’s interesting that you stuck to that quite closely with Ankara. And presumably that was deliberate, that you wanted it to still very much ring true and fit into the romance genre in that way?

BBY: Yes! It was deliberate but I think where it differs is we became very prescriptive about what they’re doing, how the men must be; the men must not be overly conceited or arrogant or thinking that in order to get the woman he must overpower her, dominate her.

ES: Yes, the guidelines are very clear, aren’t they, about both the heroine and the hero?

BBY: Yes, we don’t want to alienate people’s expectations about romance, so we wanted our messaging to be subtle. People don’t even notice the indoctrination process that takes place in a romance novel. Through the novels, you are being socialised into how you come into adulthood, how you enter and negotiate relationships. We are acutely aware of the socialising job of romance, but what we wanted to do differently was to show women that it is ok to be focused on their career as well as to desire and be desirable, to be lustful without fear. It is about giving women the permission to create the contours of their own sexual universe by providing them with representations of other women who have done it. That way, they can say to themselves, ‘I am ok to be me’. And for the woman who is waiting for some man to save her, this will show her that you don’t need to wait to be saved, save yourself.

ES: Although one of the things I was struck by when re-reading the submission guidelines was that ‘the heroine’s love interest should preferably be an African man. He is attractive and successful in his own field’. And the word ‘attractive’ there, it sort of jumped out because you don’t specify that at all for the heroine, actually. You talk about her ‘intelligence, ambition, hard work, has a bright future ahead of her’. Now, was that conscious?

BBY: Yes, because there’s a lot of attention placed on women’s body and how they look. And I was very interested in what they do, how women are represented, how they present themselves to the world, and not in a kind of corporeal sense, but more in terms of their ambition and their thought process. And I was also interested in ways in which we always talk about women’s attractiveness, women’s beauty, but we don’t really talk about men’s beauty, we don’t talk about the fact that women do look at a man purely because of his beauty. This is a conversation women have with each other, but it is not always reflected in cultural representation. We don’t talk about that. And I remember, when we first started conceiving the whole Ankara Press idea, we were very clear that we wanted the man to be attractive. You cannot have this strong powerful woman, who ends up settling for someone who’s unkempt and unattractive and somehow thinks the mere fact of being a man is enough.

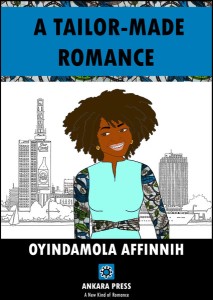

ES: And you state clearly that for the heroes ‘while standard careers and professions such as doctors, lawyers and businessmen are welcome, alternative careers such as the arts and in skilled labour…should be explored and encouraged’, and Oyindamola Affinnih’s A Tailor-made Romance absolutely explores that. But equally in three of the novels we do have very handsome, successful, immensely rich heroes, so going back to these submission guidelines, was the wealth a factor as you were editing, did it occur to you to change that at all, or to question it?

BBY: You know, I have to say, I was a bit concerned that in the very first batch of novels that came through, the men were all these wealthy, urbane type guys. And I imagine that’s because so many of the Mills and Boon stories had very successful, wealthy men. It was difficult to edit their wealth out because they were so woven into the structure of the story. Still, three of the men had unconventional careers, at least by Nigerian standards: tailor, bar manager and photographer. For the next set of stories, we’re going to say to these same authors, because they’ve all gone through the Ankara process, let’s think about it before you start, let’s think about the characters and the plot and who they are, let’s think about alternative or other non-kind of wealthy-type careers, they could be a mechanic and become wealthy, fine, but they don’t have to go through the conventional investment bank, business and finance route, they can become wealthy as an artist. They don’t even have to be wealthy, they could be just comfortable. So what would it mean to have a man who actually is not wealthy?

ES: Which A Tailor-made Romance explores.

BBY: Yes, which A Tailor-made Romance explores, even though he’s also financially comfortable, but in an unconventional way, at least within the Nigerian context. If he was in Europe, he would be a designer, you know and that’s fine but in Nigeria he’s a tailor, people don’t see that as what somebody of means would marry, so to speak.

ES: Yes, and I think actually that A Tailor-made Romance was the book where I found the heroine the most problematic because I guess, for me, I find it difficult that she was really having such a struggle to embrace the idea of a relationship with this tailor.

ES: Yes, and I think actually that A Tailor-made Romance was the book where I found the heroine the most problematic because I guess, for me, I find it difficult that she was really having such a struggle to embrace the idea of a relationship with this tailor.

BBY: And, you know, I like the fact that we see her in a turmoil, we see the way in which in this society, how we look down on certain career paths and this explores that. And one of the things I really wanted to show was that we don’t have to continue with the stereotypical femininity, nor do we have to continue with the stereotypical masculinity, so one of the things you see through the stories are examples of gentle masculinity. I think for me that was also important, for women to see masculinity as gentle. Not overpowering, to see men who are in touch with their own emotions and who are expressive and who are not afraid to own their desire.

ES: And I think in some of the books the male characters actually are the supportive, strong ones. It’s the women that, although they’re masquerading as strong, actually have the crises and the issues. And there’s a reassurance about some of these male characters, which is definitely a change.

BBY: Yeah.

ES: How many manuscripts do you think you received?

BBY: Well, we had received quite a lot, but Chinelo [Onwualu, Ankara Press editor] sieved through them. I looked at about twelve…

ES: And when you first saw those twelve, were you filled with hope, with despair, with excitement, what?

BBY: Despair actually. [Laughs]. Very much despair because I was thinking how are we going to mould them into the kind of stories that we want to publish; we cannot reject them all. Otherwise we’ll have no publishing, we’ll have no business. How are we going to make them fit into the kind of project that we want to embark on? And that was tough, but to the credit of the writers they were willing and patient enough to go on the journey with our editors. They were willing to take corrections, to be open and to take those kind of suggestions.

ES: And of those initial twelve were there some authors that you tried to work with that just didn’t work out?

BBY: Yes, I mean there’s one particular author that right to the end we worked together, we had even signed her, you know, and in the end we just had to drop her because the stories were just not going in the right way. The story, the ideas, the characters were interesting but she just couldn’t get them outside of the straitjacket of patriarchy, she just couldn’t get them… And just looking at some of the ones I read you realise how ingrained people are about how women should be and how men should be.

ES: You have chosen to launch Ankara Press as a digital imprint. Can you tell me about the reasons behind that decision?

BBY: Because of the ease of distribution. It’s an African imprint so we wanted to ensure we could reach African readers across the continent and in the Diaspora, as well as in Nigeria. There is an immediacy about publishing digitally – readers all over the globe can have access to the stories on the day of launch. And a digital imprint solves many of the distribution bottlenecks we have experienced with Cassava Republic.

ES: Finally, on the editorial side, are there things that looking back that you would have done differently when launching Ankara Press? Or advice that you would give another publisher setting up a romance imprint?

BBY: You know, we took longer than we should have. And I get that it’s also because a lot of the writers are new writers so we’ve had to really nurture them into their writing. I would say that it’s important to make sure that you have a feminist editor who understands, who can pick up the nuances, because these things will slip through your fingers. And if you are not careful you will miss it because the way in which patriarchy works is so normative that you don’t even notice, you know, you don’t notice when he opens the door, when he puts his arms out and leads her in, all of those things you don’t notice. It requires a certain sensibility to notice those things and to notice that it’s a problem, and to decide where we’re leaving it consciously and where we’re going to say, like, please change.

ES: Well, thank you so much, Bibi. And good luck with Ankara Press!

BBY: Thank you. ![]() The first six Ankara Press titles are A Tailor-made Romance by Oyindamola Affinnih, A Taste of Love by Sifa Asani Gowon, Love’s Persuasion by Ola Awonubi, Finding Love Again by Chioma Iwunze-Ibiam, Black Sparkle Romance by Amara Nicole Okolo and The Elevator Kiss by Amina Thula. The romances are being published initially as e-books and are easily downloadable to mobile devices from www.ankarapress.com.

The first six Ankara Press titles are A Tailor-made Romance by Oyindamola Affinnih, A Taste of Love by Sifa Asani Gowon, Love’s Persuasion by Ola Awonubi, Finding Love Again by Chioma Iwunze-Ibiam, Black Sparkle Romance by Amara Nicole Okolo and The Elevator Kiss by Amina Thula. The romances are being published initially as e-books and are easily downloadable to mobile devices from www.ankarapress.com.

Bibi Bakare-Yusuf is co-founder and publishing director of one of Africa’s most important publishing houses, Cassava Republic Press, which was established in 2006 with the aim of building a new body of African writing that links writers across different times and spaces. She recently co-founded Tapestry Consulting, a boutique research and training company focused on gender, sexuality and transformational issues in Nigeria. Bibi has a PhD in Women and Gender Studies from the University of Warwick.

Categories: Conversations with - interview, dialogue, Q&A

Q&A: Koleka Putuma -Revolutionising the archive and (backspace) dancing… ‘Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come in’

Q&A: Koleka Putuma -Revolutionising the archive and (backspace) dancing… ‘Hullo, Bu-Bye, Koko, Come in’  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Q&A: Publishing roundtable – #ReadingAfricaWeek

Q&A: Publishing roundtable – #ReadingAfricaWeek  Q&A: Words on… e-Kitabu – the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair

Q&A: Words on… e-Kitabu – the Rights Café, Nairobi International Book Fair

Reblogged this on Pearls & Oysters.

Reblogged this on African Stories.