By AiW Guest: Sanya Osha.

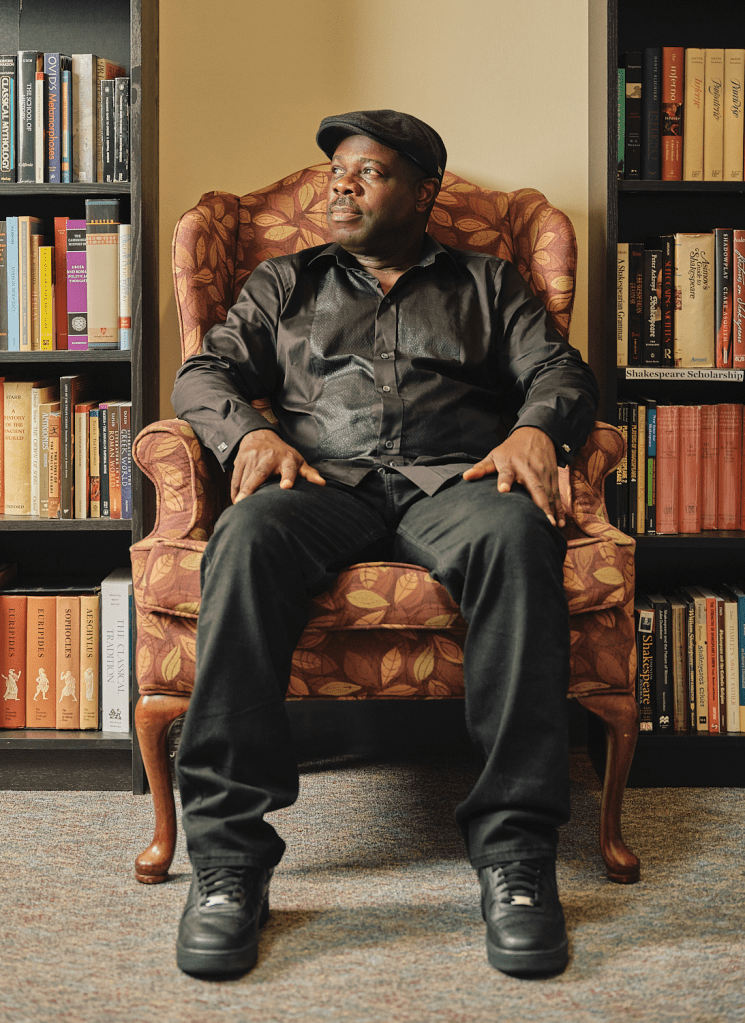

Maik Nwosu – a novelist, short story writer, poet, playwright and professor of English literary studies at the University of Denver, Colorado – is one of the more intriguing as well as enduring figures of contemporary Nigerian literature.

Although an extremely productive writer – his earlier creative works include the novels Invisible Chapters (1999), Alpha Song (2001), and A Gecko’s Farewell (2016), as well as the poetry collection, The Suns of Kush (1998), and the short story collection, Return to Algadez (1997) – he has, however, been quiet on this front for a while.

Thankfully, this has been broken, and three times over, in 2025: with the drama A Quintet for Dawn which was published in February; a poetry collection, Stanzas from the Underground, that came out in early March; and most recently, his latest novel, The Book of Everything (March 17th). On its release, I spoke with Nwosu about his writing and The Book of Everything.

To offer some background words, both to this recent novel and our conversation below, Nwosu is undoubtedly one of the most versatile among his generation of writers. He is an artist who has managed to make his mark without much of the fanfare, sensationalism or the gimmickry associated with other African authors whose careers blossomed post 9/11. That this accomplishment occurred without the seeming prerequisite approval of mainstream literary circles or international publishing muscle and marketing makes his work all the more appealing.

Additionally, Nwosu found his voice as a writer in particularly trying times in his native Nigeria. During the early 1990s, he was a senior journalist at the Lagos-based, now defunct The Sunday Magazine, or TSM for short, founded by the formidable Chris Anyanwu. Anyanwu, along with other journalists – notably, Kunle Ajibade, George Mbah, and Ben Charles-Obi – was arrested in 1995 on trumped up charges of treason after reporting on a plotted and failed coup against the nefarious General Sani Abacha regime, and faced life imprisonment, later reduced to fifteen-years under pressure from human rights groups. It was left to Nwosu and his team to keep afloat the TSM ship amid constant threats and excruciating uncertainty as the military regime’s henchmen sowed mayhem, carnage and death all over the country.

As social and intellectual life floundered under military dictatorship, the literary scene also lost much of its customary vigour. The goons of Abacha were both ruthless and relentless in bolstering the regime, and voices of dissent were extinguished either through incarceration, exile or extermination. Indeed after more than a decade of near silence, Nigerian letters began an almost unlikely resurgence, with the international recognition of diaspora authors – such as Helon Habila, who won the UK-based Caine Prize for African writing in 2001; or seen in the rising momentum of Chris Abani’s work in both poetry and prose through the early 2000s, a writer who had already gained infamy and jail time in Nigeria for supposedly prophesying a coup d’etat in literary form in the 1980s; there was Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s extraordinary reinvigoration of the scene with the publication of her ground-breaking novel, Purple Hibiscus, in 2003; Sefi Atta, and the considerable international buzz around her novel, All Good Things Will Come in 2005; or Chika Unigwe, whose novel On Black Sisters’ Street (2007/2009) won the $100,000 NLNG Prize in 2012.

Eventually, Nwosu, too, was able to extricate himself from the debris and carnage caused by military rule when he re-located to Syracuse University in the US in 2002 for post-graduate studies under the mentorship and support of Michael Echeruo, a distinguished professor of literature. Notably, the 2016 novel, A Gecko’s Farewell – which tells the stories of displacement and migratory routes of three young people, from Nigeria, South Africa, and Egypt, as they meet in the blogosphere, on a platform created by the Nigerian, Etiaba, for Africans to share their stories and community, ‘Gecko X’ – was Nwosu’s only publication of a sustained creative work after leaving Nigeria, that is, until the three book releases of 2025.

A sustained critical evaluation of the cultural lacuna in Nigeria created by military dictatorship still needs to be undertaken. A significant point of focus for such a study would be that generation of literary artists and young men whose routes and growth were impacted by the myopia and violence fostered on the ground under such rule, who were then caught up in the chasm between the stifling era and the guarded renaissance that followed after the return to democracy in 1999 – such as Obi Nwakanma, Bunmi Oyinsan, Sola Osofisan, Akin Adesokan, Uche Nduka, as well as others wedged in that awkward historical moment. Nwosu remains an important figure that wriggled out of this difficult vacuum, or emerged as a direct result of it.

It is also perhaps informative here to include the two seismic events that profoundly affected Nwosu’s generation of writers: namely, the annulment of the June 12 presidential elections in 1993 and the hanging of the Ogoni 9 two years later. Unquestionably, the country sank into a state of anomie from which it has never fully re-emerged. As a result of these pervasive crises, creatives began to betray the trust bestowed in them by the public, while others ostensibly became fully fledged political activists, with yet others succumbing to rank opportunism, sinking to dangerous doublespeak and sheer hypocrisy. Nwosu, it appears, simply protected himself from the generalised conflagration by writing; writing as a form of survival, duty and therapy. This view of writing as a means of bearing witness and as self-preservation in times of collective trauma is also an essential part of Nwosu’s art.

In The Book of Everything, Nwosu resumes his interrupted conversation with the beleaguered Nigerian nation in characteristically unflashy and clear prose. Partly composed during his fellowship at the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Studies (STIAS), South Africa, it begins with the story of Ile, a Nigerian university professor based in the US, who receives a voicemail from a man in South Africa stating that his grandfather who died forty-four years ago has a message for him.

Drawing on strains similar to animism or magical realism, we start with a conflation of life and the hereafter, the great beyond where re-vitalised spirits roam, roar and hold court, a major trope of African literature from Amos Tutuola to J P Clark Bekederemo. But nonetheless, Nwosu’s tone is mostly circumspect, his voice, mellowed and peppered by experience without the burden of undue cynicism or fire of riotous despair. Rather, his explicitly creative imaginary is infused with the wisdom of a nicely weathered elder as an even-tempered sophisticate. In the burgeoning age of Afropolitan jouissance, Nwosu resolutely remains a much-needed voice of temperance.

Understandably, the novel absorbs a great deal of Nwosu’s diasporic experience; in other words, we have a writing that is recognisably Nigerian, whilst contributing to a decidedly de-territorialised literature; efflorescent, celebratory, liberatory and often cathartic. The Book of Everything grapples with many of the defining features of Nigerian society: religious fanaticism, truncated modernity, the urban/rural dichotomy, and tussles between jarring individualism and sheepish social conformism. It is, once again, courageous ground, despite the numerous warts and discomforts belied by what it covers.

And indeed, with this latest work, Nwosu remains a sensitive and perceptive chronicler of the existential abyss looming between a state of militarised tyranny and a strikingly ambiguous post-military freedom…

Sanya Osha: You published your last novel years ago, in 2016. I take it you’ve been preoccupied with your work as an academic. In addition, you have followed a path trod by many other creative writers of your generation, transiting from journalism to academia. Can you speak about these transitions and the tensions or frustrations they have created in your literary journey?

Maik Nwosu: I was a journalist for 11-12 years in Nigeria, before I went to grad school in Syracuse, then took up a professorial appointment – first at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, later at the University of Denver in Colorado. There are different expectations in both professions. My editor used to say in those days that anyone who couldn’t meet a deadline, even an “impossible” deadline, wasn’t a journalist. That was the time when aspiring journalists were sometimes asked to go to a nearby street and come back within an hour with a publishable news story. It’s a bit of a surprise to me these days what we managed to accomplish with the limited time and resources that we had then. Some of that work would have been truly outstanding if we had more time or resources. The concern in the academy isn’t about meeting near-impossible deadlines but more about the profundity of insight that one’s scholarship offers. But journalism prepared me for the academy in this respect: I arrived in Syracuse with the ability to conduct extensive research, undaunted by any sort of deadline or volume of work. I was able to complete a rigorous doctoral program in three years. Both journalism and the academy have helped my work as a writer. Both have brought me into contact with all sorts of people and exposed me to a variety of situations, journalism more interestingly so. But they’ve also limited my concentration on my writing because both are demanding in their own ways. As a professor on the literary studies track, for instance, my creative writing is often regarded as a hobby. I’ve no doubt that I would have been a lot more productive as a writer if my trajectory or circumstances had been different.

Osha: Could you talk about the joys and frustrations of writerly life in the age of social media: do you think literature still has a place in society?

Nwosu: Yes, I think so. Perhaps I’m more optimistic than I should be – I tend to see even the deepest darkness as only a passage into light – but I don’t think that literature is about to disappear. If it ever does, our lives as humans will be diminished. Storytelling is almost as old as the history of humanity. The forms or avenues may change, but I doubt that literature will become extinct. Our world is multidimensional, perhaps more so than ever, and we need our narrative landscapes as much as we need all the other strands of our humanity. The “writerly life,” the concept of the writer and perhaps the nature of publishing, may change, but a world bereft of literary forms seems unlikely.

Osha: You used to admire the work of Egyptian novelist, Naguib Mahfouz. To what extent has he helped in shaping your earlier writings, and perhaps even your latest novel, The Book of Everything?

Nwosu: I consider Naguib Mahfouz a remarkable writer. I teach Children of Gebelawi (or Children of the Alley, as it was renamed) regularly. In 1993, when I went to Cairo, Egypt as a journalist, one of the first things I did was to go looking for Mahfouz. I’m not sure what I would have said to him if I had met him. But I was told he was in Alexandria during that period, so I never met him. I’ve written in an essay that one of the most touching incidents in African literature occurs at the end of Palace Walk, the first book of Mahfouz’s The Cairo Trilogy, when Al-Sayyid Ahmad Abd-al-Jawad is informed of the death of his favorite son, Fahmy. He goes home, deeply troubled. When he arrives, he hears his younger son, Kamal, singing with melodious abandonment: “Visit me once each year/For it’s wrong to abandon people forever.” Fahmy’s death, Al-Jawad’s contextually humanizing pain, his wife Amina’s troubling shadow, Kamal’s exultation in the supposed absence of his dictatorial father – all these weave, in one short chapter, an evocative tapestry of ironic forces and the gravity of a tragic movement of history. Mahfouz’s mastery of narrative is impressive. But I’ve never tried to write like him or any of the other writers that I admire. That’s not to say that they haven’t perhaps influenced me anyway. But I try to be innovational as much as possible. That’s a good aim. As in my previous novels, The Book of Everything attempts to aesthetically create a new or polyvalent vision of the world.

Osha: Apparently, you wrote most of The Book of Everything in Stellenbosch. What is it about the university town that attracted you in depicting it in your novel? Was it the lush landscape or its inhabitants? In short, how and/or why has Stellenbosch inspired you?

Nwosu: I have conflicting feelings about Stellenbosch. It’s a beautiful place, and the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study, my host, was outstanding. But I couldn’t get over the fact that many of the residents were white and many of those resident in the nearby township were black. And this was more than twenty years after the end of Apartheid. So, Stellenbosch didn’t inspire me in that sense. It troubled me.

Osha: The jury that judged Alpha Song, one of your ANA award winning novels, was a great admirer of your work circa 2000/2001. Jurors felt it was attempting something most other Nigerian authors missed or avoided. What were you really attempting to accomplish with that novel? Would you say you’ve departed from or that you’re still loyal to that creative blueprint?

Nwosu: The jury was quite perceptive, as is evident in their review of Alpha Song, my second novel. They saw beyond the clamor in some quarters that the novel was somehow undeserving of literary attention because of the lifestyle of some of the characters. As if puritanism is a measure of the greatness of art. Literature isn’t some sort of religious frenzy with overzealous disciples readying for a new crusade or the hysteria of a witch trial. According to these naysayers, “Literature shouldn’t do this,” “Literature shouldn’t do that.” And I ask: So, what should it do – create only characters stiff in their holiness? Why should literature hide from the flow of life, the very thing that it reflects or refracts? It should engage, and by doing so attempt to offer its readers new insights. It can’t meaningfully do this by blinding itself to all the beauty as well as ugliness in the world. The jury’s review pays attention to the aesthetic value of the novel or its existence as a work of art. The framing of that novel is important. At some point, before publication, the title was Running with the Night. To further explain my “creative blueprint” in that novel, and in virtually all my works, I often go back to the epigraph in my collection of short stories, Return to Algadez – a statement from J. M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians: “There has been something staring me in the face, and still I do not see it.” Literature can help us to see or ponder that “something” staring us in the face that we sometimes sense without seeing.

Osha: The title of your novel is most intriguing: The Book of Everything. It denotes a certain biblical sweep. What’s the reason for the adoption of the title?

Nwosu: The response to the title of the novel, “The Book of Everything,” has been almost overwhelming – so many questions and comments. I’ve had to explain that the title is not a response to any other writer’s work or a comment on the contemporary state of literature. There were other titles that I considered, but “The Book of Everything” centralizes an idea about a book of everything, which may not actually be a book, which we all have in some form – a human reality or imaginary that, while grounded in a particular experience, also transcends it. It’s not the “ten commandments” or something of that sort, but, as is the story of King Lazarus in The Book of Everything, a way of being in the world that possibly bridges the distance between zero and infinity because it’s ground zero as well as a longing for, or even a pursuit of infinity.

Maik Nwosu is Professor of English and Literary Arts at the University of Denver, Colorado, USA. He worked as a journalist and received the Nigeria Media Merit Award for Journalist of the Year before moving to Syracuse University, New York for a PhD in English and Textual Studies. His poetry collection, Suns of Kush, was awarded the Association of Nigerian Authors/Cadbury Poetry Prize in 1995. His novels, Invisible Chapters and Alpha Song, received the Association of Nigerian Authors Prose Prize and the Association of Nigerian Authors/Spectrum Prose Prize in 1999 and 2002 respectively. He has also published a short story collection, Return to Algadez; a play, A Quintet for Dawn; a second poetry collection, Stanzas from the Underground; and two other novels, A Gecko’s Farewell and The Book of Everything. Nwosu is a fellow of the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, Germany; the Civitella Ranieri Center in Umbertide, Italy; and the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study in Stellenbosch, South Africa.

Sanya Osha, a scholar and author, is currently a fellow of the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), South Africa. His latest book is An Ethos of Transdisciplinarity (2025).

Categories: Conversations with - interview, dialogue, Q&A

Q&A: Words on… Noisy Streetss’ ‘Love in Detty December’ anthology, III

Q&A: Words on… Noisy Streetss’ ‘Love in Detty December’ anthology, III  Q&A: Spotlight Interview with Ellah Wakatama, Chair of the Caine Prize for African Writing

Q&A: Spotlight Interview with Ellah Wakatama, Chair of the Caine Prize for African Writing  Q&As: Nadia Davids’ ‘Bridling’ – on the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024

Q&As: Nadia Davids’ ‘Bridling’ – on the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024  Q&As: Publishing Nadia Davids’ ‘Bridling’ in The Georgia Review – the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024

Q&As: Publishing Nadia Davids’ ‘Bridling’ in The Georgia Review – the Caine Prize Shortlist 2024

join the discussion: