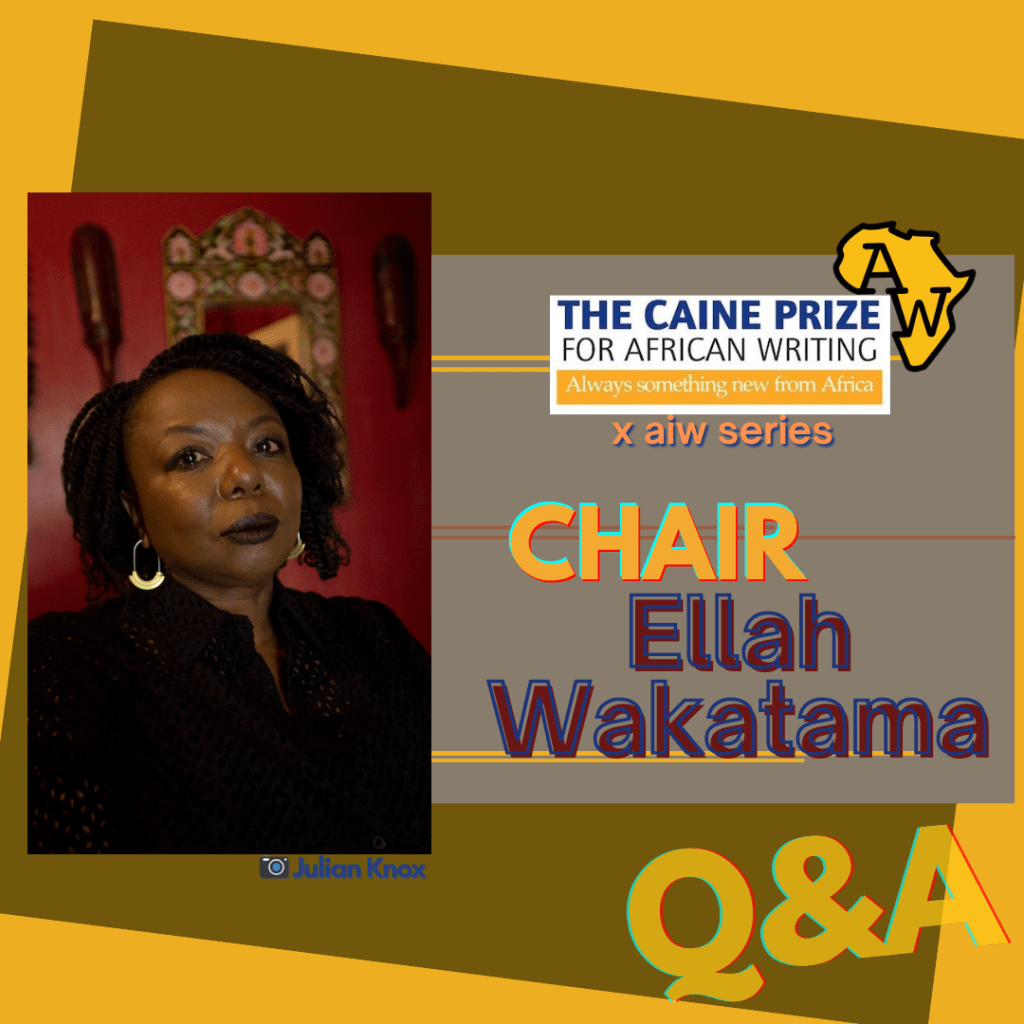

With Ellah Wakatama; interview by Doseline Kiguru.

Date: 9 December 2024.

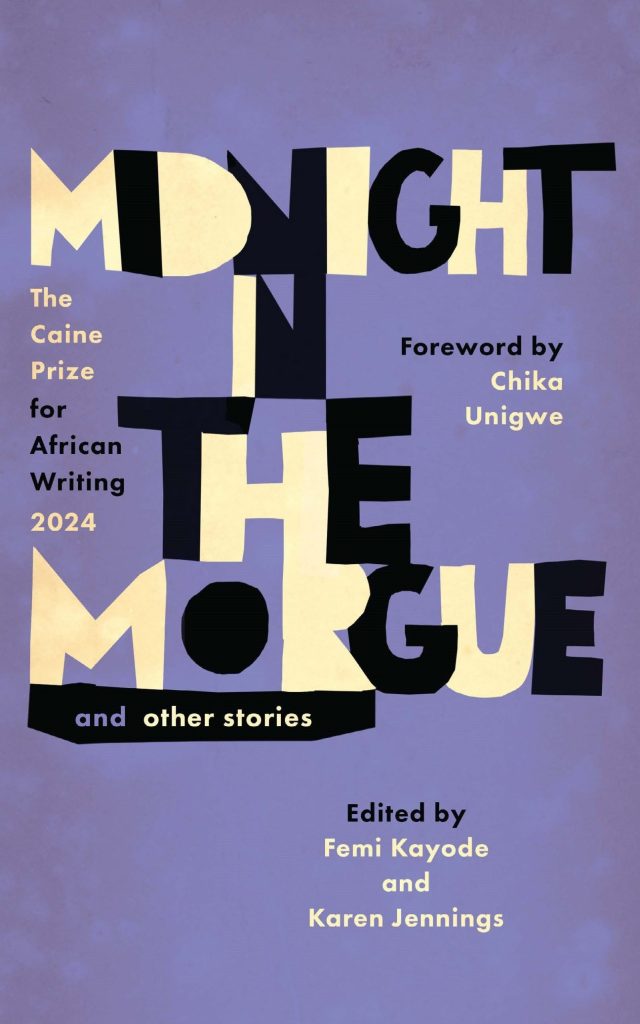

On the publication of the latest Caine Prize for African Writing short story anthology, Midnight in the Morgue and Other Stories (Cassava Republic Press), our focus on the 2024 edition of the Prize turns to look forward into 2025, the Prize’s anniversary year, as we extend our attention to the behind-the-stories, administrative level of this award.

In this interview, Africa in Words spoke to the Chair of the Prize, London-based editor and critic, Ellah Wakatama, OBE, Hon. FRSL., currently Editor-at-Large at Canongate Books and a senior Research Fellow at Manchester University.

Through this conversation, our aim was to extend our discussion beyond the literary text, and explore the different cultural and social contexts that continue to shape this Prize and platform that has become so significant for contemporary African literary production.

In “Once Upon a Time Begins a Story…” (the editorial article of the 2013 special issue of the journal African Literature Today, ‘Writing Africa in the Short Story’), the literary critic Ernest N. Emenyonu demonstrated the importance of the Caine Prize, arguing that no other contemporary cultural institution had a greater impact in foregrounding individual African writers at the global literary marketplace. Here, with AiW’s Doseline Kiguru, Wakatama takes us through her background and inspirations as a cultural producer, as well the focus and dreams for this prize body, one of the main canon producers of African literatures today.

Doseline Kiguru, for Africa in Words: Thank you so much, Ellah, for speaking with Africa in Words. We have a longstanding interest in, and have been doing a series of interviews with African literary producers, and today we’re thrilled to speak with someone heading the Caine Prize for African Writing, such a prestigious prize in African literatures.

But before we dive into that, let’s start with you: you are prolific in your field as a cultural producer, as an editor, and a critic. Can you tell us what drove you into this field? What are your passions and the background that led to this point?

Ellah Wakatama: I love that term, “cultural producer”. I think I’m going to steal it from you and use it myself — it could be my on my business card! Thank you very much to you, Doseline, and to Africa in Words, for your continued interest and support of the Caine Prize.

Starting with me… I’m the daughter of a journalist, novelist, and publisher, and in my house, books were really important. But the book I first fell in love with was The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, by CS Lewis; at the time, I was having speech therapy and we were reading that book, so it’s one of those foundational experiences and moments.

In that book, I discovered a place to escape, a place for adventure. Ever since then, reading has been my go to. Throughout my childhood, I was a “book a day” person. I always found time to read, even when I had homework to do. And I read everything; I mean, just everything. Our house was well resourced in terms of books and there was a great library in Harare.

So, I have always been in love with literature. It’s something that is very personal to me, beyond my professional work. And now, being able to reach points in my life where that personal passion is entirely immersed in my work — and not just in the books that I produce and the job that I’m paid for, but also in the work that I help support in my pro bono ventures, as in Chairing the Caine Prize – I’m very fortunate.

Also, apart from having been involved in something myself, so closely, for so many years, I like giving money to writers. I know what a difference it can make when writers are paid properly. So, being the person who is heading up something as significant as this Prize in that regard – it feels really important to me. It is something that I intentionally build in to my work life; I make time so that I can afford to be involved.

But I’m also not only excited and challenged by the reading of the works. Since I started in publishing, I’ve always wanted to be part of the decision-making processes. For too long, others decided which of our stories would be published and how they’d be disseminated. But over the last 15 years, African storytellers and cultural producers have been able to take more control over the production of our works: the editing, the publishing, the distribution of our own stories. Everything that we’re doing at the Caine Prize is born out of that passion, but also the knowledge that the behind-the-scenes work is as important as the book that you’re reading in front of you.

Doseline Kiguru: You’ve touched on a few issues that I would like to pick up on, especially about how we produce literature – the processes that bring us to the actual book. Because before we see an actual text, that you can hold and call it a novel, a short story, etc, it’s gone through a lot of production processes. A body such as the Caine Prize, along with other literary prizes, act as literary producers by influencing the canon formation process.

In the midst of those other producers, like publishers of contemporary African literatures, for example, where do literary prizes place or fit in terms of the hierarchy of canon formation bodies? – and that’s for those prizes that would be open to African writers, whether they are local African produced and funded, or whether they’re external to the continent.

Ellah Wakatama: That’s an important question. I actually think prizes rank pretty highly because that is where writers get their work amplified. And that is where we, as readers and as critics, and as anybody who has any kind of decision-making power, are able to valorise the work.

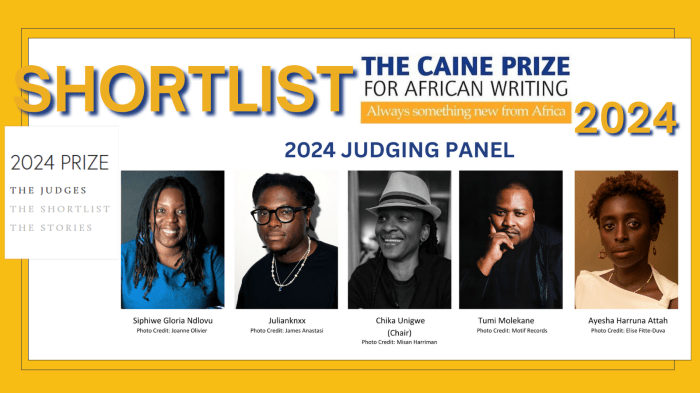

For example, for me, the most crucial part of the Caine Prize process is the selection of the judges. We strive to make that selection as varied as possible. And, to directly address your question about canon formation, when you look to the past at traditional literary canons, say, the English literary canon, those are books that were sanctioned by a very specific demographic. So I believe we have to be very conscious and intentional about what we are creating or calling our own canon, and given the continent’s vast diversity, we need to have a wide variety of voices in the room.

Under my tenure at the Prize, we’ve always made sure the judging panel includes an academic, a writer, and somebody who is from somewhere else in the artistic space, be it visual arts or dance, music, or whatever else. And we try to vary in terms of ages, and where people are living and what countries they’re from. The reason we take so much time and care over it is because it means that every year’s shortlist will reflect something different, depending on what the Chair of the judges, and each of the judges themselves, are looking for. This is why the stories on the Caine Prize shortlist can vary so much from year to year.

And so, it’s always really interesting to me when we get this conversation about what a Caine Prize story ‘is’. My hope is that, over time, people can look at the early years of the Prize and see how it has evolved, as it has been influenced by the different judges. It’s not just me or the team at the Caine Prize saying these are the stories and the writers we should all be reading. The background of how a prize is organized is really important to me in this regard.

And, let’s not forget that even a modest prize, like $100, that’s money a writer can use, whether to help pay for essentials or feed their kids, or buy themselves more time to write. So, beyond the confidence boost, the financial support is just as vital.

Even in countries where the publishing industry is well developed, only a very small percentage of writers ever make money or make a living out of writing. If a prize can offer even a small contribution to their financial well-being, it becomes important, because money matters. I think often we can get lofty when we’re talking about culture, but those beautiful stories are written by people who need to eat, take care of their families, they need lights, to pay bills – all of those things. So, for me, supporting writers financially is a huge part of what we do. And raising the money, so we can give it to the writers, that’s important.

Lastly, prizes serve as a guide to readers, a kind of pointer that we all need. I’d like to think I’m pretty good at finding quality writing on my own, but a prize will tell you, this year, this group of judges thinks that these are among the best submitted stories – and we then present them to our readers.

The publication of anthologies and otherwise sharing the stories, and the work such as that done by organizations like Africa in Words does mean that more people are aware of the writers. For us at the Caine Prize, we absolutely use the Prize as a mechanism to introduce our writers to agents and publishers. Many people have gone on from short stories to become novelists, thanks to the exposure the Prize gave them. It’s not the only way to do it, but it is a path to a wider readership. And that’s something every good writer—and some bad ones too—want, and certainly that every good writer deserves.

I see us working in different ways. In the end, I guess, the decision about how important we are will be in the results of our work.

If we look back 25 years, when I started in publishing, I had a difficult time finding contemporary African writing. Now, when you walk into a bookshop in London—or, I hope, around the world—it’s so much easier because there are so many more African writers present. In part, that’s because of the work done by prizes and other organizations that have valorised African writing. At the Caine Prize, we also focus on supporting the business of publishing alongside our work with writers.

Doseline Kiguru: You’ve mentioned the composition of the judging panel; I’ve watched it evolve, all the way from 2001 to the present. How do you think this has influenced the production and definition of the African short story?

Ellah Wakatama: I think the African short story is too big to be defined in any way at all. Each writer defines it as they are writing. My role, as someone leading a cultural organization that claims, with good reason, to be showcasing the very best work, is to make sure we are responding to and reflecting what the writers themselves are doing. So, you’ll see more science fiction on the shortlist as time passes, but that’s because writers are writing it, and some of those stories are amazing.

There are complaints every year about our selections— that’s part of how the industry works, how culture works – and those are things we take account of; we take those criticisms seriously. We discuss them as a team and, where we think we’ve made a mistake or could do better, then we do better.

But to go back to the focus of your question, I don’t think that you can define the African short story. Our hope is that, through the stories we are celebrating each year, that definition grows and becomes even more complicated to reflect the richness and complexity of our experiences.

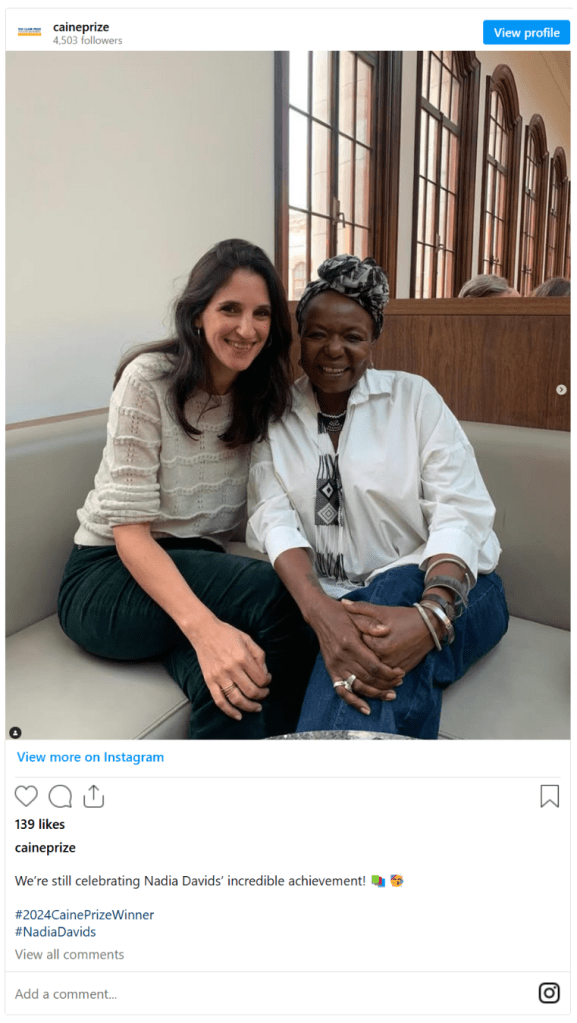

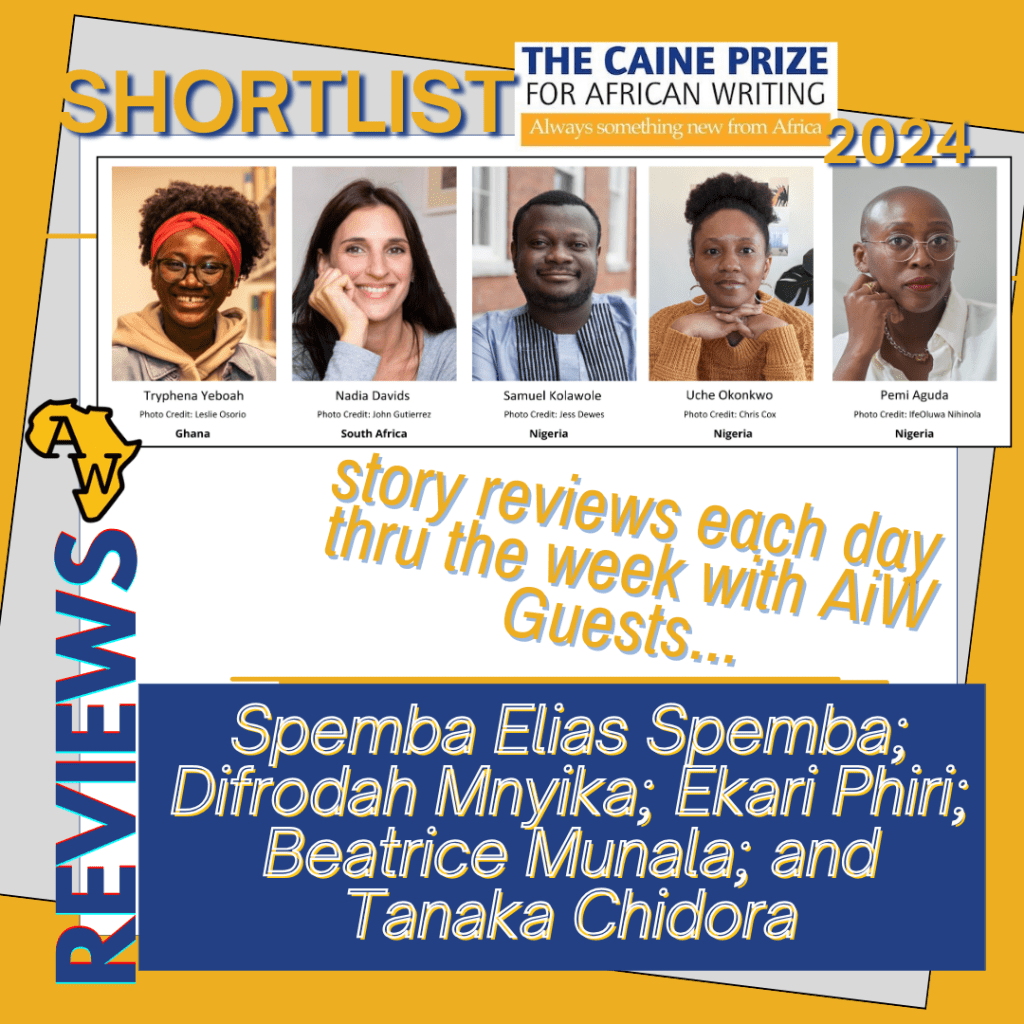

I hope that we do a good job of that. Each year the team of judges have chosen very different stories. If you look at our winner, Nadia Davids, of this year [2024] from South Africa, and the dual winners from Senegal, Mame Bougouma Diene and Woppa Diallo, the year before [in 2023], those stories couldn’t be more different. Yet they each come from a distinct African experience.

Our job is not to set the agenda. Our job is to approach this endeavour with intent, professionalism, and with joy – because we are so lucky to be doing this. All of those things go together because, in the end, what we’re doing is reflecting what African writers have already written and we are inviting the rest of the world to join us in our reading. So, we’re not setting the agenda, because that agenda, those definitions, they are made by the writers, by the creators themselves. I see our job as something different, to help elevate those voices.

The making of a canon that’s based on the idea that there’s a group of people that is better qualified than anybody else to say what reflects a culture is deeply flawed. And it doesn’t reflect the way that different African societies make decisions. I don’t know how other cultures or groupings do it, but I’m Zezuru; we are a Shona-speaking consensus building culture. We discuss things to death. It’s exhausting! But that’s how we make decisions: we talk and talk and talk until we agree.

I don’t believe that any one person, this academic at this institution, should dictate what the canon is. I am very invested in the formation of a canon and I want to be one of the people who is influencing or leading in that: I’m unashamedly ambitious in that regard – for myself, but also for our continent, and for the writers whose work I want to valorise.

At the same time, it’s part of a collective effort that is always, always led by what the writers are writing and what they want to write. If we take the lead from them, I think the books that collect together Caine Prize stories will hopefully reflect the story of a whole continent.

There’s a lot to consider in that process—like, who’s editing the stories? What support are the writers receiving? Does my judging panel include people living on the continent, not just in the diaspora? All of those factors help to ensure we are building our own model of how we proclaim and celebrate excellence.

We’re not trying to replicate the Western, often patriarchal approach to canonical culture and excellence, a model that’s worked really hard to exclude us for long. We’re not going to join into that exclusionary process.

What we’re doing is entirely different, and while I can’t define it precisely for you, each year we get closer to a definition and, curiously, the closer we get, the more we see it complicate and expand.

Doseline Kiguru: When you look at the history of literary prizes and the prestige that comes with them around the world, most focus on longer works of fiction. There are fewer prizes for short stories, poetry, and other short forms. But the Caine Prize has become a significant award for African literature, specifically focused on the short story. Where do you see the future of the short story—not just on the African continent, but in wider literary markets?

Ellah Wakatama: Every year, you will find publishers, academics, critics saying that short stories are too difficult; they’re hard to sell; the short story’s dying. But it relentlessly carries on and it shape-shifts, and as readers, we continue to love them. I can’t possibly predict what’s going to happen but I do think that in today’s digital age, short stories will mutate in fascinating ways. People are consuming information so much more quickly, and short stories are well-suited to that shift.

And this is something, at the Caine Prize, that we’re trying to keep up with at this stage. We publish our stories online, and while the writers are compensated, the stories are available for free. As a charity, that’s a challenge. It expands our readership in ways that wouldn’t be possible if people were having to buy a print novel in their home countries – we recognize that not everyone can afford books, especially in many countries on the continent where they can be so expensive.

I don’t believe in publishing work for free because writers must be paid at every stage of their work. But I do believe in organisations such as ours being able to pay the writers and disseminate their work to a wider audience, as widely as possible. To sum it up, that can be an introduction into a writer’s work, but for some readers, the free, online short story might be the only way that work can be accessed.

So, while I can’t predict the future, I can say the short story isn’t going anywhere. However, I am disturbed by the lack of a Pan African literary prize. Please correct me if I’m wrong – I know there are various book prizes on the continent, but I don’t know that there’s one that’s pan African, including the diaspora of African citizens, and that’s not even to speak of the wider, more historical diaspora. I think this is problematic. There has to be a way to celebrate and valorise in a way that brings readers from all over the world to these works. It’s a much more difficult endeavour. Running a prize for a full book is far more costly than one for a short story, given the time judges need to read, for one.

But I don’t think having a short story prize excludes celebrating longer works. Any reader will tell you they want both: they want the short stories and the novels, as well as works of nonfiction.

Doseline Kiguru: Can we speak about the Caine Prize’s relationships with African publishers mostly, and specifically, about the Caine Prize workshops, both the editing workshops and the creative writing workshops? How have these kinds of structures and deliberate connections influenced the quality of work that eventually gets submitted for the prize?

Ellah Wakatama: Those are three distinct things, all working toward the same goal. When Dr. Lizzy Attree was the Caine Prize administrator – a role that has since changed: we now have a director rather than an administrator, as well as an administrator – when she was looking after the Caine Prize, she initiated collaborations with publishers on the continent where we would provide the anthology as a fully edited, typeset PDF to selected publishers for free, and they would then produce and sell it commercially.

Over the years, the number of partner publishers on the continent has grown, and it’s something we hope to expand to cover more countries, funds permitting, because it’s been really successful. I’ve always been clear that I don’t believe in giving away books for free. There has to be some acknowledgment of the business behind it. So, when we give the PDF, there’s no money exchanged, but we have invested our money, our funds as a charity. That money comes from our funders and donors.

We invest the money in the making of the book and our hope is that, in not charging the publishers we work with, they can invest in developing their industries in their countries. They sell the books commercially at affordable prices, which hopefully creates a greater appetite for these stories and helps to bolster their own costs, so they can continue to publish local writers as well.

That’s the way we hope we are contributing to the building of local industries. These publishers will then encourage more writers, who will then participate in the Caine Prize, and we can amplify those stories. Being part of that ecology, because we have the resource and we also have the experience to be in collaboration with publishers — that collaboration is crucial to me.

Moving on to one of our longest-running initiatives – the creative writing workshops. These workshops are really about giving writers a space to work with people who are their contemporaries and who are also internationally successful authors. What we’re saying is, These are people who are just like you, from different African countries, but with levels of experience that you can learn from. And for that period of ten days, it’s intense; I mean, the writers work really hard in our workshops. They arrive with an idea for a story and leave with a completed one.

Our hope is twofold. One, that they build a sense of community with other participants because this is vital for a thriving literary ecology, a group of writers who can support and amplify each other’s work, but also give each other encouragement. Two, that they receive editorial support, which is one of the things that has proven very difficult to come by for writers on the African continent. The situation has improved enormously thanks to the amazing journals and the different literary initiatives emerging across the continent that are now focusing on giving that editorial support – we’re not alone in this. But that’s one of things we hope our workshops achieve.

Another benefit of the workshops is that they produce stories we can feature in the Caine Prize — So, you didn’t make the shortlist, but we can offer the workshop, which generates amazing work. We select broadly for the workshops – the Caine Prize team (not including me) makes the selection. Some participants are writers who the judges have said show great promise but didn’t make it to the shortlist – we want to continue to support them; some are writers who have been shortlisted; we always offer it to past winners; and we ask for recommendations from our peers on the continent. We try to make it as wide-ranging as possible to offer the most benefit and support.

As for that narrative of ‘the single story’, it’s something I hope and believe we’ve moved away from, and I’m confident in that. Ajoke [Bodunde, Administrator at the Caine Prize] will tell you that each year, the team is really exercised when we announce our shortlist and the criticism starts coming in. And I think it’s great. It means people are engaging with what we’re doing. I want to hear the criticism. Some of it is ill-informed, but much of it we can learn from. So, I don’t mind that at all.

The last point I’d mention is our online editorial workshops, which are run by Vimbai Shire, who is a British Zimbabwean editor and was Interim Director of the Prize up until a short time ago. This initiative began under the leadership of Delia Jarrett-Macauley when she was Chair of the Prize – she really spearheaded it and I continued to develop it after taking over. We were concerned that, year in, year out, we could see that the stories being submitted by journals on the continent were not making it to the shortlist. This wasn’t because the writing wasn’t good—because as editors, you know when a story is unpolished but is still very, very good – and yet, we kept seeing that the winners were coming primarily from outside the continent.

Now, I don’t have a problem with that because I am an African who doesn’t live in an African country, and that doesn’t diminish the essence of who I am. But at the same time, we found this concerning because we are not a prize for the diaspora: our focus is on the African experience on the continent, as well as that diaspora. The issue wasn’t a lack of talent—it’s there in abundance. We knew the problem was that the editorial support those living in cities like London, New York, or Berlin were receiving wasn’t as readily available for the writers living and working on the continent. We wanted to make that editorial support available. And so, again, we leveraged our resources and found personnel to address that gap, something that we saw as a problem.

The online writing workshop is a response to that. It provides an opportunity for writers who may not have made it to the main workshop, or who can’t afford to pay an editor, or who want to make sure they are getting the best editorial support. We select on that basis, using all the channels I outlined before, offering them editorial help and then seeing what they produce as a result of it.

All three of these initiatives work in tandem towards the same goal.

Doseline Kiguru: As we conclude, I would just want to ask you about your highlight moments at the prize –moments, texts, events.

Ellah Wakatama: I make sure that the team doesn’t tell me who’s won. I don’t read anything until the shortlist is announced, because my face doesn’t hide anything. I don’t have any influence over the judges – I certainly spearhead the choosing of the judges, but beyond briefing the Chair of the Judges, I don’t read the submissions. When the shortlist comes, I read the shortlist. But on the night of the Prize, I also don’t know who has won. So, for me, my highlight every year is working really hard for this goal, and at the same time, giving the judges complete and utter freedom to do what they want.

Now that means that sometimes the winner I picked in my head is not the judges’ pick. Which is great. I can’t be the one who’s in charge of it – as I said, the definition has to be wide. My highlight happens each and every year when the winner is announced and I am just so happy. I’m so happy to hand over the cash. I’m inevitably always proud of my team, even in a year like this, where we’ve had to consolidate – looking forward to our 25th anniversary celebrations, and also because we’re in a period of quite intense fundraising right now to ensure the future of the Prize. That moment of announcing the win and giving away the money makes sense of all of the work that we’re doing. It makes everything make sense, and it’s a moment of complete and utter joy before we start the grind again, and it gives me life. So that’s my highlight.

Doseline Kiguru: The Caine Prize has been around for 25 years. We have seen it grow. We have seen its shortcomings and its positive influence on the African continent. What do you think the dream is for the Prize in the next 25 years?

Ellah Wakatama: At the moment, I am thinking much more short term than that. My job right now is to ensure our next five to 10 years and that is really about money. We have been working really hard to diversify our funding and to make our funding more Africa-based. We’re talking about all of these other projects and things we can do. But we can’t do any of that if we don’t have the money. So, for me, that securing of our financial future is the most important thing.

Going beyond that, I don’t think the Caine Prize will expand in ways that mimic others, because I think, in many ways, we have inspired lots of new initiatives, and lots of new initiatives have grown, either as a counter or to complement the work that we do. I’m really supportive of all of those organisations and in any way that we can, we try to work together. I think we all are working towards the same goal.

At the same time, as Chair, I certainly don’t want us to be duplicating other people’s efforts, so we will continue to focus on the things that we know we do well and that our experience means we do best: our workshops and our online editing mentorship. We definitely want to grow those and experiment with maybe having more of the workshops on a regional basis, perhaps having them online. Any expansion will be really focused on things that are already part of the Caine Prize DNA.

At 25 we are grown now – you know, this is the age at which you’re expected to pay your own rent and do all of those things! The Caine Prize of 25 years ago is not the same as the Caine Prize now. I am very grateful to the founders because they’ve certainly impacted my career, in terms of the writers I’ve had access to, or have found through the Prize, or the writers that I had found on my own whose work was then amplified by awarding them the Prize. There’s a lot of gratitude for that, but the Prize did need to become more African.

We are based in England now and I think one of the things that we hope funding will allow us to do is to award the prize on the continent rather than in London, and as soon as we can afford to do so, we will do that. Our Board of Directors – when you look at it now and look at it five years ago, it’s just a very different board. A lot of the members of the Board had been with the Prize since the beginning, and that’s a lot of dedication, a lot of time that they gave. But at the same time, I wanted to make sure that there were voices there that were African-born, and that were black as well. That was really important to me.

To clarify, I am not one of those people who thinks you have to be black to call yourself African. I think people of different races who’ve lived on our continent for generations are African too. So that’s not what I mean, but the Board did have to reflect the majority of African peoples. And that’s something we’ve achieved. We’ve got a really energetic and involved Board. I think that is showing in our shift in focus, and rather than saying our back is to the continent and we’re showing it to the world, it’s turning around and looking more closely at the continent itself and wanting to be more organically connected without denying what our roots are.

Because there’s no point in denying what the roots of the Caine Prize are. We can’t pretend that we’re anything but what we are. I’m proud of it. I’m proud of the work that’s been done and feel very honoured and gratified to be able to head up the organisation and take it into the future.

Doseline Kiguru is a researcher with an interest in literary texts and their production mechanisms. Her research engages with cultural and literary production in Africa with a focus on different literary platforms such as publishing and prize industries, book fairs and festivals, literary magazines and writers’ organisations, exploring the networks they create and the effects that they have on contemporary African literary production. She is currently a Lecturer in World Literatures at the University of Bristol.

Today marks the last post in what has become our annual Caine Prize coverage for 2024, which includes:

- a series of our twinned ‘Words on / Caine Prize Q&As’ with the Chair of the Judges, each of the shortlisted writers, and some of their publishers, cross-referencing and opening up their involvement in the 2024 award;

- and a complementary series of reviews of each of the stories on the shortlist, written for us by critics based on the continent, commissioned by our own Wesley Macheso (Reviews Editor).

Browse the full series via our homepage or click here.

With congrats and thanks to all our Q&A Caine Prize Shortlist 2024 participants; thanks to our reviewers for such careful readings of the stories nominated to the shortlist, and to Wesley Macheso for their commission; and special thanks to Ajoke Bodunde and Ellah Wakatama at the Caine Prize.

For more on the Caine Prize, and to read all the shortlisted stories, visit: https://www.caineprize.com/.

All our 2024 coverage –

Words On / Caine Prize Shortlist Q&As (above)

Story Reviews by critics based on the continent (below)

– find them, with all our Caine Prize critical coverage so far (back to 2013!), here…

Categories: Conversations with - interview, dialogue, Q&A, Reviews & Spotlights on...

Spotlight on… Editing Anthologies: Doorways, Communities, and Reference Texts

Spotlight on… Editing Anthologies: Doorways, Communities, and Reference Texts  Spotlight Q&A: Editors & Writers talk – Ucheoma Onwutuebe’s ‘Where Are You and Where Is My Money’, with Lydia Mathis

Spotlight Q&A: Editors & Writers talk – Ucheoma Onwutuebe’s ‘Where Are You and Where Is My Money’, with Lydia Mathis  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Review and Q&A: Leila Aboulela’s ‘River Spirit’ – Rewriting the Footnotes of Sudanese Colonial History

Review and Q&A: Leila Aboulela’s ‘River Spirit’ – Rewriting the Footnotes of Sudanese Colonial History

join the discussion: