AiW Guest: Florian Stadtler.

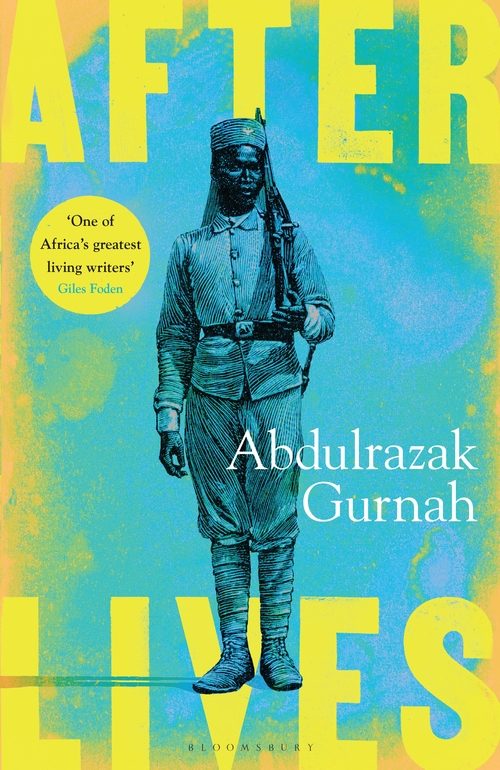

‘Taking up where his 1994 Booker finalist novel Paradise left off, Abdulrazak Gurnah transports his readers back to the First World War in his latest novel Afterlives. This coming-of-age novel follows the unanchored adolescent lives of Ilyas, Hamza and Afiya disrupted by the war in the early twentieth century, and interrogates the personal and political cost of rebellion.’ (Africa Writes — Exeter Book Club)

AiW note: Stadtler’s review is the third in a series of AiW posts introducing Abdulrazak Gurnah’s latest novel Afterlives (Bloomsbury, 2020) in the run up to the third Africa Writes Exeter Book Club event, on March 30th 2021, 4-5 pm (BST). For details of tix and registration – see below.

![]()

See more at Bloomsbury: https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/afterlives-9781526615879/

German colonial history remains little explored in fiction. Since the 1880s, Kaiser Wilhelm II, grandson of Queen Victoria, had the ambition to secure what was then termed Germany’s ‘Platz and der Sonne’, its place in the sun, Von Bülow’s infamous phrase in praise of Germany’s expansionist colonial policies. In popular historical discourse of German colonialism, attention tends to focus more on Deutsch-Südwestafrika, now independent Namibia, and especially the 1904-08 genocide of the Herero, Sana and Namaqua people by the local Schutztruppe, the German colonial troops. On the African continent, Germany’s colonial empire included Cameroon (1885-1916), Togo (1884-1914), and Deutsch Ostafrika (German East Africa) (1885-1918), which comprised modern-day Tanzania, Burundi and Rwanda. Notable in these dates is that Germany loses control of its colonies at the beginning and during the First World War.

Afterlives is set in the run up to, during and after this world-encompassing conflict. The story revolves around Ilyas, Hamza and Afiya. Both Hamza and Ilyas are recruited into the Schutztruppe askari, the infantry division of German colonial forces in German colonies on the African continent. While Gurnah tackles world historical events which deeply impact his characters’ lives, he is equally interested and focused on their everyday experiences. The novel teems with striking descriptions of Afiya’s daily chores, or Hamza’s ordinary day, working as a carpenter after his return from the First World War:

‘Hamza broke fast with Khalifa on the porch where in the traditional way they shared a few dates and a cup of coffee and were then called inside to the modest feast Bi Asha and Afiya had prepared and which they sat down to eat with the men. It was not the quantity but the variety of dishes that made it into a feast, and they talked about the food and praised its preparation as they ate. Even Bi Asha was more mellow than she had been in the past and found teasing words to say to Hamza about his growing skills as a carpenter and his newfound fame as a reader of German.’ (195)

Aftermaths as much as afterlives, then, become a driving narrative force in this novel — structured around memories, often painful, and shaped by traumatic experiences of violence. In that sense we encounter characters who are engaged in a process of rebuilding their lives, of their instinct for survival, of wanting to live and find reasons to carry on, and to seek contentment in the ordinariness of life. This is best exemplified by the slowly developing courtship, romance and eventual marriage of Afiya and Hamza, lyrically and tenderly described. It is here where Schiller’s Romantic poetry, translated by Hamza for Afiya from German acquires new resonances. Hamza is initially tutored by his German commanding officer to read German and is gifted Schiller’s Musen-Almanach für das Jahr 1798. He then goes on to transcribe and translate some of these poems for her: “He wrote them out on the piece of paper he had stolen from Nassor Biashara’s office, trimmed it so that it was only just big enough for the verse, then folded it so it was no wider than two fingers. He knew how it would look if this scrap of paper were intercepted.” (192)

This novel is also one of interstices, enmeshed in the brutal experience of German colonialism as well as the aftermath of that experience, as much of German East Africa is placed under British administration as a League of Nations mandate and renamed Tanganyika after the war. In that respect, Gurnah also explores the multiple shifts in European territorial inscriptions on the African continent after the First World War.

In Afterlives we can trace a number of recurring themes from Gurnah’s previous work. On the one hand, there is the novel’s explorations of memory, trauma and loss, and on the other, further explorations of the innocence of childhood and how adolescence and early adulthood are shaped by experiences of a brutal system of oppression, be it in the military or by association with merchants and traders. Here especially, Afterlives reads like a pertinent follow-up and companion volume to his 1994 Booker Prize short-listed Paradise. For example, Yusuf’s journeys to the interior from the coastal regions, its pre-war setting and its elements of Bildungsroman, and the way in which Gurnah confronts his readers with the complexities of layered cross-cultural experiences and encounters very much resonate. In Paradise the German colonial rulers’ callousness and cruelty is relayed as rumour and hearsay; in Afterlives it is firmly brought into view.

As Afterlives moves through time from the immediate aftermath of the war through the 1920s, into the 1930s, 40s, 50s and 60s, the question of what happened to Afiya’s brother, Ilyas, who, like Hamza is a former Schutztruppe askari, becomes the major narrative driver. The process of how his fate is revealed through snippets of information highlights the importance of artefacts and the archives — letters, diaries, chance encounters, and of course official records. This enables Gurnah in the final reel, now in post-Second World War Germany, to fully reveal Ilyas’s story of settlement and life and his brutal treatment in Nazi Germany. Here, there are perhaps some analogies with the life of Bayume Mohamed Husen, a former Askari who settled in Berlin, first working as a waiter, then as a bit-part film actor.

Gurnah is unsparing in his detailing of violence and colonial atrocities. What makes this historical novel a tour de force is that it unflinchingly brings to life in fiction the reality of a colonial experience, of which many in Germany show little awareness or an unwillingness to fully confront it. The brutalising system of the Schutztruppe askari so callously deployed by German colonial authorities across their empire is brought into sharp relief here. They are described “a highly experienced force of destructive power. They were proud of their reputation for viciousness, and their officers and the administrators of Deutsch-Ostafrika loved them to be just like that” (8). These descriptions are often delivered by the omniscient narrator with matter of fact sobriety, crystalline in the outlining of the system of cruelty designed by the German colonial administrators and officers, and reinforced through the interactions and exchanges between characters, relaying in dialogue the details of atrocities and consequent reputation of the askari. This enables Gurnah to explore in depth the systematic brutalisation of the askari themselves, their impact on the local population, the aftermath of the experience of the war on his two central characters, and the legacies of the First World War in East Africa.

I sincerely hope that this brilliantly plotted novel will receive a German translation in due course. This is a must-read for a country which still has much work to do as part of its Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung – the process of working through the past – to fully acknowledge its brutal colonial history overseas. Here, too, Afterlives in its title resonates in multifaceted ways, revealing Gurnah as the master storyteller he is. Through the power of fiction and the novel as form he opens up new pathways for an honest dialogue about these histories, the legacies of colonial encounters and the consequences of the First World War and its afterlives on the African continent and in Germany.

![]()

C. Mark Pringle

Abdulrazak Gurnah is the author of nine novels: Memory of Departure, Pilgrims Way, Dottie, Paradise (shortlisted for the Booker Prize and the Whitbread Award), Admiring Silence, By the Sea (longlisted for the Booker Prize and shortlisted for the Los Angeles Times Book Award), Desertion (shortlisted for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize) The Last Gift and Gravel Heart. He was Professor of English at the University of Kent, and was a Man Booker Prize judge in 2016. He lives in Canterbury. (c. Bloomsbury)

Florian Stadtler is Senior Lecturer in Postcolonial Literatures in the Department of English and Film at the University of Exeter. He has published articles and books on Salman Rushdie, Indian Cinema, South Asian Writing in English, and Black and Asian British film, history and literature. He is Reviews Editor of Wasafiri: The Magazine of International Contemporary Writing. Twitter: @FloStadt

Florian Stadtler is Senior Lecturer in Postcolonial Literatures in the Department of English and Film at the University of Exeter. He has published articles and books on Salman Rushdie, Indian Cinema, South Asian Writing in English, and Black and Asian British film, history and literature. He is Reviews Editor of Wasafiri: The Magazine of International Contemporary Writing. Twitter: @FloStadt

![]()

You can find our first post on Afterlives, by Judyannet Muchiri here – ‘“Such noise and screams and blood”: a review of Afterlives’

Judyannet’s follow up is a conversation with Gurnah for AiW, which delves into Gurnah’s craft, community, memory & war, with Gurnah’s finding and so drawing out the “unexpected kindnesses in the story” (Gurnah) – ‘Q&A with Abdulrazak Gurnah about latest novel ‘Afterlives’: “These stories have been with me all along…”‘

![]() Get your tix for the Afterlives Africa Writes Exeter Book Club (30th March 2021):

Get your tix for the Afterlives Africa Writes Exeter Book Club (30th March 2021):

Praised by Giles Foden as ‘one of Africa’s greatest living writers’, award-winning author Adbulrazak Gurnah will be in conversation with Novuyo Rosa Tshuma to discuss the power and essence of how compelling characters drive a story forward in Afterlives. We welcome you to join us even if you haven’t read the book! In fact we have an excerpt you can delve into beforehand, check it out right here.

And you can read our AiW review of Tshuma’s House of Stone (2018), ‘Zimbabwe’s substitutions, or: what difference would a good or bad past make?’, by Ranka Primorac here:

House of Stone is a story of bemusement and horror; hilarious subterfuge with tragic undertones. Reading it feels like being punched in the stomach and tickled at the same time.

Ranka Primorac.

![]()

Afterlives is published by Bloomsbury. For more details and availability, see https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/afterlives-9781526615879/

Categories: AiW Featured - archive highlights, Reviews & Spotlights on...

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  AiW long read: Caine 2021 – A prize coming of age

AiW long read: Caine 2021 – A prize coming of age  Celebrating World Poetry Day with readings from Wreaths for A Wayfarer

Celebrating World Poetry Day with readings from Wreaths for A Wayfarer

join the discussion: