AiW Guest: Sarah Ahrens

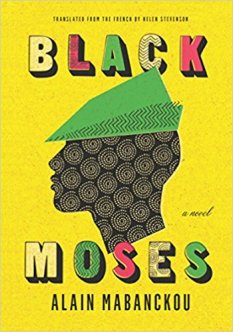

The first thing that struck me about the English translation of the latest novel of Francophone Sub-Saharan Africa’s arguably most successful living writer was its title: Black Moses is quite a departure from the original French Petit Piment (“Little Pepper”). Black Moses brings to mind Soul legend Isaac Hayes’ 1971 album of the same name or, more recently, D’Angelo’s Black Messiah (2014). Whether a stylistic choice or editorial decision to market the English translation to a U.S. audience, in any case, the title locates the novel and the reader in a North American cultural context. Four decades of Black music, from Hayes to D’Angelo, echo forty years in the life of Moses. Mabanckou’s eleventh novel (and the eighth one translated into English) recounts the adventures of this young man, from teenager to forty-year-old, who lives through his country’s eventful history of the 1970s. The proclamation of the Marxist-Leninist People’s Republic of the Congo in 1969 – a Soviet-style single-party state– which lasted until 1991 and which was replaced by the more-or-less uninterrupted rule of President Denis Sassou Nguesso.

Black Moses interestingly explores Congolese history and literature and the notion of a world literature in French. But, it falls far short of delivering on a plot level, as the female characters are underdeveloped and the novel’s conclusion plays into a contrived and predictable narrative about post-independence African nations and identity.

Black Moses interestingly explores Congolese history and literature and the notion of a world literature in French. But, it falls far short of delivering on a plot level, as the female characters are underdeveloped and the novel’s conclusion plays into a contrived and predictable narrative about post-independence African nations and identity.

Like his biblical namesake, Mabanckou’s Moses is a foundling. An unlikely prophet, he grows up in an orphanage in Loango, a small place near the harbour city Pointe-Noire. The institution represents a microcosm of the People’s Republic and announces Moses’ first-person narrative as a “history from below”. Populated by those at the bottom of society, the orphanage is ruled by its director, Dieudonné Ngoulmoumako – the phonetic proximity between “director” and “dictator” works even better in French. Indeed, the flowery adjectives and repetitive quality of French bureaucratic rhetoric seem to satirise the novel’s broader political context; a quality that is more noticeably absent in English. The director-dictator is thereby less of a biblical pharaoh than a quintessential party official. He is a dull and violent opportunist, devoid of any ideological conviction, who has found ways to benefit from the political system:

His presence on the platform was like a staged event of such mediocrity that the strings were visible the moment he communicated with the wardens opposite him with clumsy eye-winking, which we all could easily interpret. (15)

His description can certainly be seen as a nod to the Republic of the Congo’s most significant writers of the twentieth century, such as poet Tchicaya U Tam’si (1931-1988) or Sony Labou Tansi (1947-1995), whose novels such as L’Etat honteux (1981, The Shameful State) or L’Anté-peuple (1983, The Antipeople) often depict the absurdity and grotesqueness of autocrats and kleptocrats, who have little interest in the well-being of the people they are ruling over.

However, part of Black Moses’s historiography is also the protagonist’s life story: Moses joins the twins Songi-Songi and Tala-Tala in running away to Pointe-Noire, leaving his best friend Bonaventure behind to escape the orphanage they perceive as a prison. In Pointe-Noire, Moses encounters a fellow petty criminal, who fashions himself as Robin Hood, in outfit and behaviour. Moses himself will adopt this persona towards the end of the novel, and the Robin Hood theme is echoed by the cover illustration, which is reminiscent of the Jamaican reggae artist Barrington Levy’s Robin Hood LP (1980). The novel is peppered with references to canonical works of European literature, from Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers (117) to Cervantes’ Don Quixote (161). This comes as no surprise: ten years ago, Mabanckou was one of the signatories of the “Manifeste pour une littérature-monde en français” (“Manifesto for a world literature in French”). The pamphlet postulates the idea of a “littérature-monde” to erase the hierarchical differentiation between “French” and “Francophone” fiction. However, a number of critics, especially in the UK and the US, have voiced concerns as to whether the term does little to actually challenge the ideological and economic realities that marginalise writers of colour. Mabanckou’s references then raise questions of the continuing predominance of Euro-American readership, publishing houses, and the immediate effects these have on circulation, translation, and validation (note that all of Mabanckou’s novels since 2003 have been published by the prestigious Paris-based Editions du Seuil).

The novel, as with the canon, remain dominated by a pervasively masculine sense of narrative voice. We do get to know Sabine Niangui, who takes care of Moses at the orphanage. She is regularly abused by the director, briefly tells Moses her life story, and then vanishes. We also learn about “Maman Fiat 500”, who runs a brothel in Pointe-Noire. She helps Moses off the street, but also disappears. The book loses her narrative during one of the city’s mayor François Makélé’s populist “cleansings”, when Zairian sex workers are subjected to mass rape, killing, and displacement. What is disappointing is that all female characters are represented rather stereotypically as either subjected to sexual exploitation by men, as surrogate mothers to Moses, or both. They all disappear, and the repeated traumatic experience of loss and abandonment by a maternal figure fuels his subsequent descent into madness.

The novel, as with the canon, remain dominated by a pervasively masculine sense of narrative voice. We do get to know Sabine Niangui, who takes care of Moses at the orphanage. She is regularly abused by the director, briefly tells Moses her life story, and then vanishes. We also learn about “Maman Fiat 500”, who runs a brothel in Pointe-Noire. She helps Moses off the street, but also disappears. The book loses her narrative during one of the city’s mayor François Makélé’s populist “cleansings”, when Zairian sex workers are subjected to mass rape, killing, and displacement. What is disappointing is that all female characters are represented rather stereotypically as either subjected to sexual exploitation by men, as surrogate mothers to Moses, or both. They all disappear, and the repeated traumatic experience of loss and abandonment by a maternal figure fuels his subsequent descent into madness.

In the Hebrew Bible, the Prophet Moses is also a writer (for example, in Deuteronomy 31:22). At the end of the novel, we learn that Moses himself has narrated his story to us while being incarcerated in a psychiatric detention centre for killing the mayor of Pointe-Noire. Incidentally, we are back in Loango, since the facility occupies the same site as the orphanage Moses grew up in. It is here that he reunites with his best friend Bonaventure (however, due to their withered mental state, they don’t recognise each other).

The ending seems a bit expected, and Black Moses as a whole provides its reader with an exploration of identity that follows a well-trodden path in African post-independence writing. While the novel is certainly not Mabanckou’s best work, it introduces Anglophone audiences to a re-evaluation of ideas of kinship and ethnicity via the cityscapes of Pointe-Noire, Congolese cuisine, and state institutions, through the visions the novel’s eponymous prophet.

Born 1966, Congo, Alain Mabanckou is a prolific Francophone Congolese poet and novelist. He currently lives in LA, where he teaches literature at UCLA. He is the author of six volumes of poetry and six novels. He is the winner of the Grand Prix de la Littérature 2012, and has received the Subsaharan African Literature Prize and the Prix Renaudot. His previous books include African Psycho, Broken Glass, Memoirs of a Porcupine and Black Bazaar. In 2015 he was listed as a finalist for the Man Booker International Prize.

Born 1966, Congo, Alain Mabanckou is a prolific Francophone Congolese poet and novelist. He currently lives in LA, where he teaches literature at UCLA. He is the author of six volumes of poetry and six novels. He is the winner of the Grand Prix de la Littérature 2012, and has received the Subsaharan African Literature Prize and the Prix Renaudot. His previous books include African Psycho, Broken Glass, Memoirs of a Porcupine and Black Bazaar. In 2015 he was listed as a finalist for the Man Booker International Prize.

Sarah Ahrens is a Postdoctoral Research Assistant for the AHRC-funded research project ‘African Reading Cultures: Popular Print in Francophone Africa’ at the University of Bristol. She also serves as an Impact Evidence Administrator within the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures. She received her Ph.D. in French from the University of Edinburgh, focusing on representations of the city of Brussels in contemporary Francophone diasporic literature.

Sarah Ahrens is a Postdoctoral Research Assistant for the AHRC-funded research project ‘African Reading Cultures: Popular Print in Francophone Africa’ at the University of Bristol. She also serves as an Impact Evidence Administrator within the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures. She received her Ph.D. in French from the University of Edinburgh, focusing on representations of the city of Brussels in contemporary Francophone diasporic literature.

Categories: Reviews & Spotlights on...

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’  Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)

Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

join the discussion: