AiW Guest: David Borman

Emmanuel Dongala in 2011

I first encountered Jazz and Palm Wine in fragmentary form. As a student who read French poorly yet took a course on Francophone African Literature, I was allowed to read translations of our coursework, and one assignment involved Dongala’s Jazz and Palm Wine. Little did I know that only the short story of the same name had been translated into English at that time. It was included in a volume of science fiction—named after the short story—compiled by Willfried Feuser. I was confused as to how a collection of stories by authors from across Africa could be a classic of Congolese literature. This April, Indiana University Press released the first English translation of Dongala’s entire collection Jazz and Palm Wine, which has been available in French since 1982. I am no longer confused as to why the collection as a whole a classic.

All of the book’s stories stand where ways of life intersect. Of course, jazz and palm wine come from two distinct cultural traditions, yet in Dongala’s stories the mingling of those traditions seems natural, almost inevitable. The governmental desire to “progress” on an international scale is pitted against the cultures that continue to govern life in villages across Dongala’s African landscape. The artistic impulses of jazz are reckoned with the political and social revolutions Dongala’s narrators link themselves to.

The first five stories take place on the African continent, in a country that feels—in its references to the concepts of “scientific socialism” and the Marxist-Leninist state—similar to the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville) during its decades of postcolonial rule by Alphonse Massamba-Débat and Marien Ngouabi. In “Old Likibi’s Trial,” representatives of the scientific socialist state—which has rejected all forms of thinking not aligned with a secular and socialist perspective—must come to terms with the fact that it has not rained in the months since a village man divined the rain to stop. In the man’s trial, the justice explains the rationale for seeking a judgment against him: “The party leadership wants to demonstrate that natural causes alone cannot be blamed for our lagging development, but that in addition to the stranglehold of big business over our economy, it is the backward mindset of a number of peasants that is to be blamed” (43). This and the collection’s other earlier stories—notably “The Ceremony” and “Comrade Kali Tchikati”—capture the absurd and terrifying aspects of a national government that puts ideology above its people.

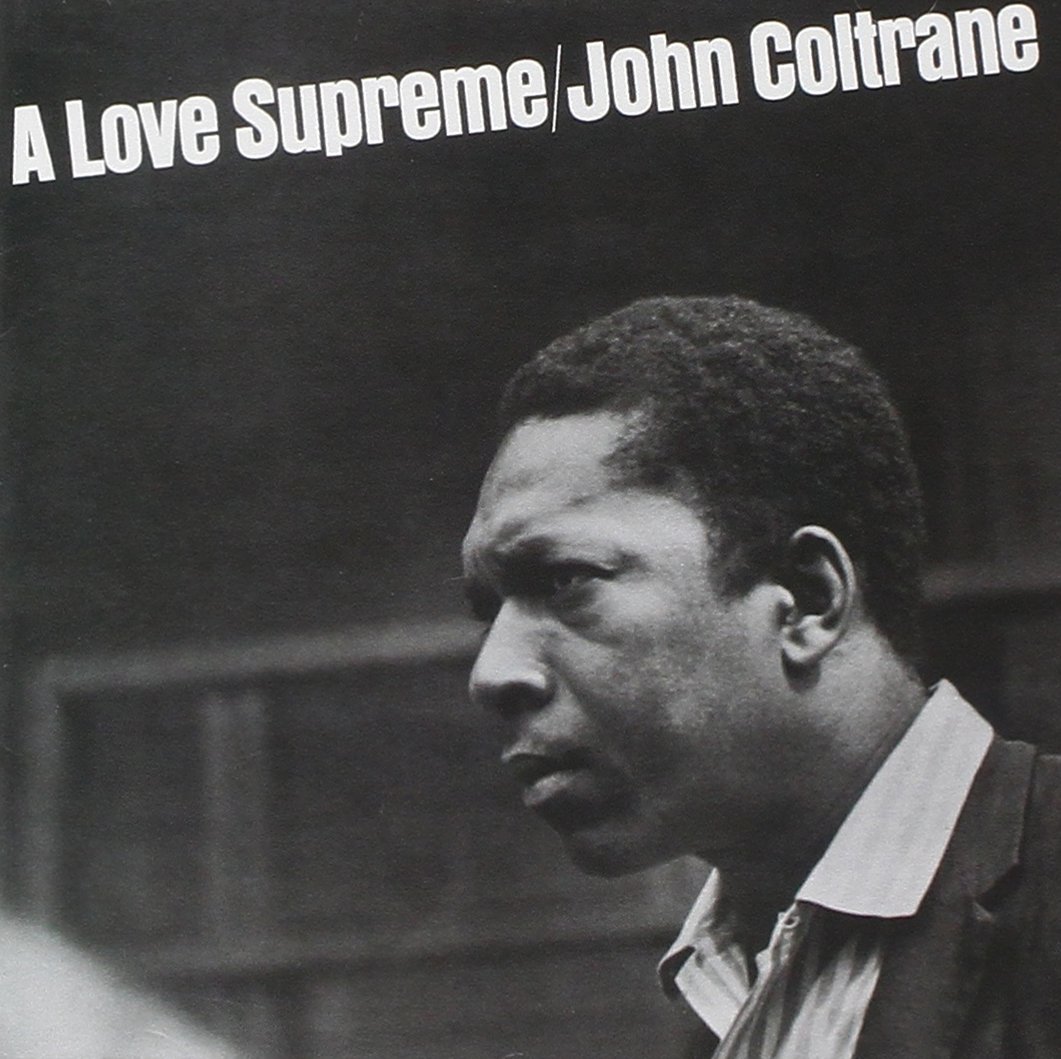

“Jazz and Palm Wine,” the title story, is the thematic centerpiece of the collection, combining the daily life Dongala sees in Congolese villages with jazz music. There are also aliens, who come to earth seeking domination and can only be appeased by listening to John Coltrane and Sun Ra records while drinking palm wine. Although a number of nations propose solutions to the alien invasion, those of the African delegation convince world leaders that holding a palaver with demijohns of palm wine is the best way forward. In the end, Coltrane is canonized, Sun Ra is president of the United States, and jazz has conquered the world.

The book ends with some shorter pieces, taking place in New York City and concerning jazz music. The final reflection, “A Love Supreme,” is simultaneously sad—the loss of John Coltrane that begins the story can be felt deeply—and joyous. Dongala’s narrator describes the experience of hearing Coltrane play and the intellectual challenges his music presented to its audience. And these moments are magical. He describes the final concert he hears Coltrane perform: “We no longer existed. We too were transported on this journey along with the Master, the witch doctor: a great pagan feast, a Dionysian feast, hell and damnation, sulfur and salt, love, salvation. We’d been stricken and transfixed. We bathed in a world of sublime supreme love” (112).

The quality of this book is no surprise, given Indiana UP’s record with translating African literary works into English. The translation feels fresh and alive, while the introductory material by Dominic Thomas gives a great sense of Dongala’s work in detailed biographical and historical contexts. The publication of an English version of Dongala’s collection would be something to celebrate in itself. But when combined with the concerted effort of IUP to translate major Francophone African authors into English, this new version of Jazz and Palm Wine means just a bit more. Since its inception, IUP’s Global African Voices series has translated Sony Labou Tansi’s Life and a Half; Alain Mabanckou’s Blue White Red; multiple works by A.A. Waberi; and Boubacar Boris Diop’s stunning novel Murambi: The Book of Bones. The recent translation of Dongala’s collection is a natural next step for this consistently quality series of books, and it is a fantastic read on its own too.

Emmanuel Dongala is Richard B. Fisher Chair in Natural Sciences at Bard College at Simon’s Rock. His novels have been awarded the Grand Prix Ladislas Dormandi, the Grand Prix Littéraire d’Afrique Noire, the Charles Oulmont Prize, and the Cezam Literary Prize.

Dominic Thomas is Madeleine L. Letessier Professor of French and Francophone Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. His books include Nation-Building, Propaganda, and Literature in Francophone Africa; Black France: Colonialism, Immigration, and Transnationalism; and Africa and France: Postcolonial Cultures, Migration, and Racism.

David Borman is the reviews editor for Africa in Words for 2017-2018. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Miami and teaches courses on literature and writing at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky.

David Borman is the reviews editor for Africa in Words for 2017-2018. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Miami and teaches courses on literature and writing at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky.

Categories: Reviews & Spotlights on...

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’  Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)

Review: Connection and Legacy – Remembering ‘Before Them, We’ (2022)  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

Review: Tragedy and Resilience in Lagos – The Truth About Sadia by Lola Akande

join the discussion: