I’ve recently picked up Tim Parks’ collection of essays Where I’m Reading From: The Changing World of Books (2014). One of the essays in Part 2, ‘The Book In the World’, entitled ‘Writing Adrift in the World’, critiques post-colonial literary studies:

‘I tutor students from England, studying, or practising, creative writing. They too now move in an international world… They too have taken courses in world literature, or at least post-colonial literature. They are familiar with the big international names – Kundera, Pamuk, Eco, Vargas Llosa, Roth, Murakami. They know who won the Nobel, the Man Booker International Prize, The IMPAC, the Pulitzer. Exciting as it is, Pamuk,for example, may offer a strong sense of place, but it is one increasingly addressed to those outside Turkey, rather than to the Turkish themselves; is the young English writer to talk about England to a foreign audience?’

He goes on (at some length) to argue for the significance of a geographically specific literary canon, as something addressing the problem of:

‘a slow weakening of our sense of being inside a society with related and competing visions of the world to which we make our own urgent narrative contributions’ being replaced by ‘the author who takes courses to learn how to create a product with universal appeal, something that can float in the world mix, rather than feed into the immediate experience of people in his own culture’.

Parks, ‘Writing Adrift in the World’.

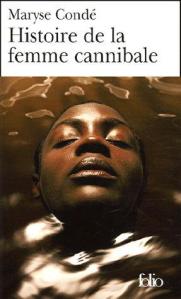

I’ve been thinking how odd this line of criticism is after reading Maryse Condé’s 12th novel, The Story of the Cannibal Woman, originally published in 2003. This is a book set in Cape Town, written by a Guadeloupian woman, who now divides her time between the US and France (the book is translated into English from the original French, Histoire de la Femme Cannibale, by Condé’s partner, Richard Philcox).

Elizabeth Schmidt in her essay, ‘Magical Thinking‘, argued that the ‘essential question’ of The Story of the Cannibal Woman is outlined from the start:

‘What happens when a woman who feels she can’t get out of bed must get out of bed? What happens when a black, childless woman, from Guadeloupe originally, with no source of income, finds herself stranded in a rich white neighborhood in Cape Town?’

Schmidt, ‘Magical Thinking’, New York Times, April 15th, 2007

Whilst I would agree the ‘essential’ frame for the book is a death, a man, Stephen’s, who goes out to buy a packet of cigarettes one night and never returns, and his widow, the woman Schmidt identifies above, Rosèlie’s mourning process, it is also unquestionably much more ambitious and far-reaching than this, using the personal to ask questions about relationships, migration, history…

What do you do with the past. What a cumbersome corpse! Should we embalm it, idealise it, and let it take over our destiny? Or should we hurriedly bury it as a disgrace and forget it altogether? Should we metamorphose it?

Condé, The Story of the Cannibal Woman, pp.120-121.

Condé’s wiki pages mention her autobiographical influences, and her feminist commitments. Like her protagonist, Rosèlie, a painter, Condé has lived and worked in the creative industries in Francophone Africa, after a period of study in France, moving there from Guadaloupe. Here, the character of Rosèlie is used to present us with questions about the complex post-apartheid politics of relationships in South Africa, how couples can have completely different views of their experiences, as well as exploring ideas about home and relocation.

In places, this crosses similar territory with British writer Zadie Smith, in exploring the uncomfortable aspects of how people can live together when dealing with the realities of racism in societies that aren’t as accepting as the national publicity brochures claim.

As Rosèlie tries to find out how she can mourn Stephen and the police question her account of his death, we learn more about their journeys, separately and together as a couple. She sets herself up as a clairvoyant and psychic, meeting with other travellers and residents, scarred by their experiences of South Africa, of migration, as her clients. She is shown as using her ‘gifts’, subtly understanding their troubles, offering healing, even as she struggles to resolve her husband’s motives, his choices, not least on the night of his death.

Rosèlie presents one story to us early in the book, of meeting Stephen — he, a British ‘white guy’, a ‘University Professor. Taught Irish literature’; she, a black woman and painter, who replies to him: ‘Me? Nothing! A man has just left me high and dry…I’m trying to survive and cure myself’ (p.14) — in a fictional city in Francophone Africa, ‘N’Dossou’:

He used to work in London. Listening to him, Rosèlie was as fascinated as if an astronaut had described his days on the MIR space station. So people spend their time wallowing in fiction, getting worked up about lives they have never led, paper lives, lives in print, analyzing them and commenting on these fantasy worlds. By comparison she was ashamed of her own problems, so commonplace, so crude, so genuine. (p.14)

As the novel develops, this cliché of a pick-up is undermined, both by her memories of Stephen and the investigation into his death. The police ask her questions about the night he is murdered that hint at a late night meeting; she tries to find out more through his former students, his colleagues, and issues around race and racism are brought to light; Condé takes us through a series of social events and dinner parties of the past where Stephen becomes an increasingly unpleasant figure, pushing Rosèlie into life and career choices, antagonising her friends by deliberately challenging their opinions.

Condé’s resolution to the ‘puzzle’ of Stephen is more obvious to the reader than it is to the ‘gifted’ Rosèlie, who greets the police revelations with shock. More complex, and unresolved for us, are the reasons she was with him in the first place, why she was tethered to him for so long, way beyond his initial ‘rescue’ in N’Dossou, on through their journeys and life, and latterly her isolation, in their rich white neighborhood in post-apartheid Cape Town, in a range of shared spaces that are reflected through other scenes that take place, for example, in the internationalised city sites of Tokyo and New York.

Condé’s work is acclaimed, both nationally and internationally, recognised for her entire body of work most recently by the Man Booker International shortlist for 2015. So, does this make her a target for Parks’ list of what I see from his essay as ‘not particularly useful’ writers vis-a-vis the anchoring value of a ‘national tradition’ for a writing student, a list that, in addition to those cited in the first quote from Parks above, includes the problems of ‘mixing Chinua Achebe with Primo Levi’ (‘Writing Adrift in the World’)?

I don’t know how Parks’ students might react to or challenge his skepticism of their value to their reading of ‘world’, or ‘post-colonial’, fiction. Perhaps they are in on, and know (as I don’t), whether he is ‘simply’ being provocative in his position as a writer of essays for the NYRB. Either way, I would encourage them to consider this book in light of ‘national’, postcolonial’, ‘world’ writing, in my seat as a reader first, and as an international one after that.

For more on The Story of the Cannibal Woman, see:

A relatively academic style but accessible review of Condé’s book in American Book Review (July/Aug 2008), by Marie-Helene Koffi-Tessio, available on the link in the title below (including an explanation of the ‘cannibal’ reference):

‘Of Cannibalism. On Maryse Condé’s The Story of the Cannibal Woman‘

Parks’ original published article in the The New York Review (2012):

‘Writing Adrift in the World‘

Reading Group Guide from the publisher of this edition, Simon and Schuster, with a summary and a set of 10 discussion questions.

Categories: AiW Featured - archive highlights, Reviews & Spotlights on...

Spotlight on… Editing Anthologies: Doorways, Communities, and Reference Texts

Spotlight on… Editing Anthologies: Doorways, Communities, and Reference Texts  Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’

Archives spotlight – Past & Present: Maryse Condé – ‘Segu’ and ‘The History of the Cannibal Woman’  Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)

Words on…Past & Present: The International Black Speculative Writing Festival (London & Remote)  AiW long read: Caine 2021 – A prize coming of age

AiW long read: Caine 2021 – A prize coming of age

This does sound like a wonderful book.

I am frustrated by Park’s argument. I am a white male reader in Canada with a strong interest in international and foreign fiction. The criticism that writers are increasingly writing for an international audience is spurious and offensive. Not only are readers increasingly international, so are writers. White South African writers for example have often been accused from within the country for not addressing post apartheid issues every time they put pen to paper. It is important, yes, but so are other universal themes that inspire writers to write and readers to read. Does Parks have a problem with the fact that so many “international” writers – Latin, Chinese, African, Indian and so on – have read widely in the English and American literary canon? Do writers read Dostoevsky to learn about Russia or because there is a fundamentally timeless quality to his work?

Many international writers do not live in the countries in which they grew up or that inspires their writing. Sri Lankan-Canadian writer Shyam Selvadurai has spoken about the problem of definition for international writers. He argues that sometimes the only place such a writer can write from is the hyphen. As a Canadian I am rarely engaged by highly localized writing. I am however intrigued to see how writers from elsewhere employ Canadian settings. I am also fond of writers who have migrated to Canada but address that experience and/or set their work in their country of origin. Arguing, as Parks does, that Pamuk should be writing for Turkish audience to tell them what they know is akin to saying Turkish readers should only read indigenous Turkish literature. Why translate anything at all?

Sorry for the lengthy comment.